PROVIDENCE CARE - MENTAL HEALTH SERVICES SITE

Construction of Rockwood Asylum began in 1859 to house the "criminally insane" of Kingston Penitentiary. The Asylum's site overlooking Lake Ontario was thought to have a calming effect on patients. The new limestone edifice - still situated near here - began accepting non-criminal patients in 1868. Rockwood became part of the Ontario provincial asylum system in 1877.

Kingston Penitentiary convicts were conscripted to build Rockwood. Architect William Coverdale's progressive design featured larger rooms with windows and some common sitting rooms. Rockwood also had one of the first central heating systems in Canada, deemed safer than stoves and open fires.

Tourist Attraction

Rockwood's architecture and beautiful site were a point of civic pride for Kingstonians and regularly featured on postcards in the early 1900s. It was also a popular stop for visitors and the curious. As one superintendent wrote in 1882 after the crush and confusion of one public day when 1000 came to view the asylum: "We have been deluged with visitors." These visits may have helped people to understand the mentally ill better and break down some boundaries, since by then patients were actively involved in work-therapy and recreation programmes.

Rockwood Asylum: Early Beginnings

In the latter part of the nineteenth century, there was a distinct shift in the institutional care and treatment of people identified as being mentally unsound. Across Ontario, imposing institutional asylums replaced the gaols that had formerly housed patients/inmates. A movement away from brutal confinements, tortures, and various medicinal treatments (including alcohol) coincided with an emerging understanding of mental illness as a disease that could be treated.

In turn, asylums began to be transformed from warehouses for the insane into genuine treatment facilities, becoming full-service hospitals for formal study and treatment.

Reformer medical superintendents Dr. William Metcalf (1878-1882) and Dr. Charles Clarke (1882-1905) were heavily influenced by the work of Dr. Joseph Workman, the long-time superintendent of the Toronto provincial asylum (1853-1875). Dr. Workman's therapeutic method reflected prevailing Victorian practices of psychiatry.

Improvements in living conditions

Rockwood was a self-sufficient community with almost all of its staff and patients living and working together on one isolated site. This was thought to create a protective environment for patients at Rockwood - a sanctuary away from the world. The institution's strict controls also served to keep inmates away from the rest of society.

Physical Restraints: In 1878, patients were confined within the asylum and 10% of residents were also locked into personal restraints. Dr. Metcalf's first reform was to remove most restraints, which resulted in "less excitement, fewer injuries, less destruction of property and much more peaceful wards."

Clothing: Dr. Metcalf also eliminated the use of canvas clothing, which had previously been worn by residents who were deemed “lunaticsâ€

Health Care: In 1893, the asylum constructed Beechgrove, a full-service medical infirmary for patients with acute diseases and for convalescent patients.

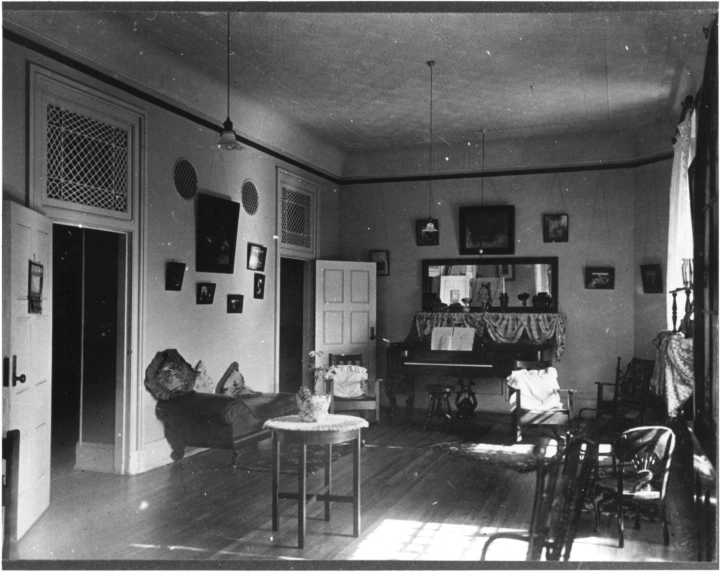

Accommodations: Rockwood was outfitted with painted rooms, improved bedding, and sitting rooms with beautiful furniture and decorations. Several cottages were constructed on the asylum grounds so some patients could live in more home-like surroundings, depending upon their classification (chronic vs. acute, for example).

Meals: Dr. Metcalf provided patients with ceramic plates and cutlery, replacing the tin cups and spoons they had been using. Menus began featuring a broader choice of items. By 1892, the Asylum had bought neighbouring Newcourt farm and had begun producing its own food to help reduce the cost of meals for patients and staff.

Religion: Worship was a regular part of life for patients and staff. There was access to services for both Roman Catholics and Protestants.

Education: In the late 1880s, a school opened for female patients, as many of them were illiterate. Dr. Clarke wrote, "Schools are now recognized as a necessity in the modern asylum..."

Early Years

In the mid-1800s, the main medical goal was to calm rather than to cure patients. Excited patients were sometimes "bled" to calm them. Chloral hydrate was a favoured drug to pacify patients, but alcohol was also commonly administered.

Under a moral-therapy programme, the virtues of work, religion, regularity, order, and punctuality were instilled in patients as means of "treatment". Asylum officials were always challenged to balance their therapy programmes for patients with minor illnesses with those treatments best suited to long-term patients.

Changing Approaches

Even without physical shackles, patients might be controlled in other ways. The newly popular hypodermic needle made it easy to sedate patients with addictive drugs such as morphine. Other available sedatives and hypnotic drugs in the late 1800s were bromides, chloral hydrate, paraldehyde, sulphonal, and barbital (amyl nitrite). Victorian concerns about sexual behaviour made some restraints, such as masturbation-preventing devices, more acceptable than others.

The first formal lectures in psychiatry at Queen's University began in 1895 and Rockwood staff helped train the medical students. Although training was improving, there was still little scientific knowledge available about diagnosis and treatment of mental illness. During this period, physicians may have performed some of the first neurosurgical procedures on Rockwood patients using such tools as trepanning sets (trephines) to drill into a patient's skull.

After 1900, the emphasis in psychiatry moved from "non-interventionist" therapeutic approach (moral therapy) to the "classification" therapeutic approach stressing scientific methods. One of these new methods was continuous bath therapy (hydrotherapy) used to soothe patients by suspending them for an extended time in warm rushing water.

I'm "cured"; what now?

Patients who left Rockwood Asylum still had to struggle with fear and possible rejection from their former communities. As early as the 1890s Dr. Clarke advocated a system of aftercare outside the hospital following a patient's discharge.

Work as Occupational Therapy

Under moral therapy, it was believed that regular, steady work and a good diet would lead toward regular, steady, and rational habits and away from mad thoughts. Good physical and mental health would therefore lead to a sane mind.

At Rockwood, women generally worked inside, providing meals, tidying wards, and cleaning clothing and linens. Men laboured outside in grounds maintenance, agriculture, stone-masonry, and woodworking.

This unpaid, involuntary labour served a dual purpose for Rockwood administrators; it helped control violent behaviour of patients and so decreased the use of physical restraints, and it also kept the asylum operating, since the number of paid staff could be reduced. Kingston Asylum was praised for its sound work programme - over time, this evolved into occupational therapy.

Recreational Activities for Patients and Staff

The moral therapy philosophy advocated recreation to divert patients from "brooding over their real or imagined misfortune". Recreational activities were also good for staff morale.

Female inmates always got less physical exercise than men. In the 1870s, Dr. Metcalf had women's "airing courts" built to allow them to get outside. In 1890 Clarke introduced "physical-culture classes" for women - calisthenics put to music on the asylum piano. This activity helped violent and delusional women ward off violent outbursts.

Sports for both patients and staff included hockey, curling, baseball, boat races, bowling, football, and the new fad of bicycling.

By the 1890s, patients could enjoy magic-lantern shows, outings to town, rides on a chartered steam yacht, and the asylum band. There were clubs for photography, bird watching, sketching, and drama. The 14-piece asylum orchestra organised by Dr. Clarke and his family was considered the best in Kingston. Under Dr. Clarke, musical talent was an important skill for new employees as well.