Introduction

What are Vaccines? Why Bother?

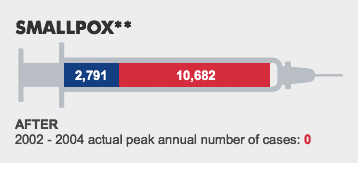

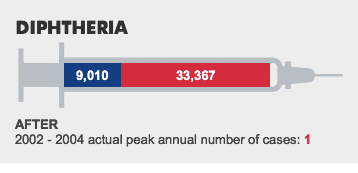

Vaccines are carefully designed to prevent people from contracting specific diseases, especially infectious or communicable diseases, such as smallpox, diphtheria, polio and pertussis, although there are many others. Vaccines also prevent people from becoming carriers and passing such diseases on to others.

The development of vaccines was inspired by the observation of a simple fact: in most cases, once a person gets a disease they do not get it again. Certain cells in your immune system learn to recognize what an invading virus or bacterium (‘bug’ for short) looks like. They can do this because these ‘bugs’ have unique protein shapes on their surface. The next time that particular disease comes around, your body is ready to fight it off before it gets a chance to make you sick.

Essentially, a vaccine tricks your body into thinking you already had that disease. In fact, vaccines are made from killed or weakened virus or bacteria, or key pieces of them – just enough to get your immune system to learn to recognize it, but not cause disease.

In rare cases, an individual may have an allergy or sensitivity to a specific vaccine, and some people may react in other minor ways, particularly near where the vaccine is injected. But vaccines are a highly tested and regulated medical product – they are the most regulated - and reactions to them are very rare. The suffering and death caused by the diseases and the large numbers of people they can affect, especially young children, far outweigh the generally small risks from vaccines.

Canada Post stamp celebrating 50th anniversary of the Salk polio vaccine, 2005.

Canada Post stamp celebrating 50th anniversary of the Salk polio vaccine, 2005.Image Source: Sanofi Pasteur Canada.

Also see Museum of Health Care accession #005025001.

Intensive research is ongoing into developing a wide variety of new vaccines to protect against long-standing and increasingly serious infectious and other types of diseases. However, as the primary focus of this online exhibit is historical, to learn more about how vaccines work, the science of immunology, and the wide range of new vaccines being developed, consult the Resources section for direction to a selection of useful websites.