Polio

“The Crippler”

Poliomyelitis – a.k.a. “The Crippler” or “infantile paralysis” - is a viral disease that primarily, and quite harmlessly, infects the gastrointestinal system. But if the poliovirus survives and is able to enter the bloodstream and nervous system it can cause damage to motor neurons in the spinal cord that connect the brain to muscles. Such damage interferes with muscle control, causing weakness or paralysis. The arms and legs are most often affected, but the muscles that control swallowing and breathing can also be weakened or paralyzed, this type of “bulbar” polio putting the patient’s life in danger. The “iron lung” was developed to treat patients whose ability to breathe was affected, using negative pressure to force the chest to expand in and out.

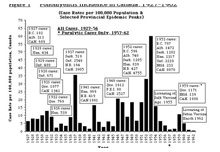

Polio incidence in Canada, 1927-1962

Polio incidence in Canada, 1927-1962Christopher J. Rutty, “Do Something! Do Anything! Poliomyelitis in Canada, 1927-1962” (Ph.D. Thesis, Department of History, University of Toronto, 1995).

Though an ancient disease that seemed to strike young children quite randomly, polio became a growing epidemic threat in the industrialized world during the late 19th and early 20th centuries, ironically, as public health and sanitary standards improved. Since the poliovirus reproduces in the intestinal tract and spreads primarily through oral-fecal contact, greater attention to personal and public hygiene resulted in the virus circulating less evenly amongst infants, and thus fewer developed natural immunity to the disease. Thus, over time, a growing percentage of children, as well as young adults, particularly among the more hygienic middle class in small towns and new suburban areas during the postwar “baby boom,” were vulnerable to the poliovirus, which had a greater chance of invading the nervous system and causing paralytic damage.

Until the mid-20th century, and despite the “modern” medical science of the period, polio remained a scientific and public health enigma, relentless in its spread and in its personal, physical, economic and political impact. While epidemics worsened, there was little progress in understanding how the disease spread or how it could be prevented until the late 1940s when a series of major scientific breakthroughs, several made in Canada, opened the door to the development of a polio vaccine during the early 1950s.

Image source: Library and Archives Canada (public domain image)

Personal Perspectives on Polio

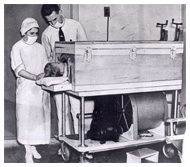

Gordon Jackson in the “wooden lung,” Hospital for Sick Children, Toronto, 1937

Gordon Jackson in the “wooden lung,” Hospital for Sick Children, Toronto, 1937Image source: Hospital Archives, The Hospital for Sick Children, Toronto (used with permission)

No two cases of polio are the same since the damage the poliovirus can cause along the long stretch of the spinal cord (specifically the “anterior horn” or grey matter part), is quite random. And depending upon the severity of the damage and its location, the effects can range from slight weakness in a hand or foot, to paralysis in a leg or arm muscles, to impairment of the chest or diaphragm muscles that control breathing. Thus the personal experience of polio is quite individualistic.

Gordon Jackson with a portable respirator, Hospital for Sick Children, Toronto, 1937.

Gordon Jackson with a portable respirator, Hospital for Sick Children, Toronto, 1937.Image source: Hospital Archives, The Hospital for Sick Children, Toronto (used with permission)

Here are a few perspectives on the polio experience based on differing severities and age of onset at selected times during the epidemic era in Canada.

Gordon Jackson was almost 4 when he was stricken with polio in August 1937 during Toronto’s worst polio epidemic. The disease paralyzed his limbs, but more alarmingly, he soon began to have difficulty breathing. The Hospital for Sick Children only had one “iron lung” and a young girl was dependent upon it and it would be a couple of weeks before another would arrive. Gordon’s case highlights how polio could progress rapidly and how its threat could prompt quite extraordinary efforts to fight it. With Gordon’s breathing weakening, a small experimental respirator designed for premature infants was found and the hospital’s engineers and carpenter scrambled to build a larger wooden cabinet in about 5-6 hours. By the time this “wooden lung” was ready, Gordon was almost blue and his breathing very laboured. But after two hours of the lung helping him breathe, his colour returned to normal and he was eating. As the polio epidemic continued and more bulbar polio cases were likely, the hospital began an unprecedented effort to build iron lungs in the basement. Gordon was soon able to leave the “wooden lung” for an iron lung, and was then given a new portable respiratory jacket. A newspaper report nine months later noted that Gordon was free of any devices to help him breathe, but had to remain in hospital.

Video source: March of Dimes Canada (used with permission)

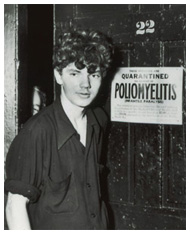

Jeannette Shannon was 11 when she was stricken with polio in 1947, and within 24 hours of the onset of high fever, headache and stiff neck, was in the isolation ward of a Hamilton hospital. “I was a very young child,” she later recalled, and “I had never been away from family before. By accident I was put in a women’s ward instead of the children’s.” Jeannette would remain in the isolation ward for the next 6 months, totally paralyzed. She had four-limb paralysis and partial facial paralysis and stayed in the hospital for close to two-and-a-half years. “It was a horrific time. We were the AIDS patients of the ‘30s, ‘40s and ‘50s. People were terrified of polio.” Some 10 years of physiotherapy followed and eventually she was able to lead a normal life. However, like many polio survivors, some 30-40 years after the original polio infection, Jeannette experienced a return of the pain and weakness of the disease with “post-polio syndrome.” For more information about post polio syndrome, visit the Post Polio Canada website.

Jeanette Shannon shares her personal polio experience in this video produced by the Ontario March of Dimes and the Paul Martin Sr. Society in 1999 and entitled 'A Most Honourable Legacy'

"Listen to Jeanette Shannon and polio historian, Christopher Rutty, discuss the history of polio in Canada on CBC Radio's "Morningside" from April 12, 1995 on the 40th anniversary of the introduction of the Salk polio vaccine."

Image source: (public domain image)

Click here to learn more about Neil Young's polio experience

Neil Young & Joni Mitchell, the noted Canadian musicians, both were stricken by polio, Neil first in 1951 in Omemee, Ontario at age 5, and Joni in 1952 in Saskatoon, Saskatchewan at age 9.

For Joni Mitchell, polio made her “prematurely adult and stubborn.” “The polio ward is a really depressing place,” she remembered, “and you hear the whining of the iron lungs, a bunch of them going away, and you’re just praying that you don’t go into one. The disease only rampages for two weeks and then you’re left with the disaster. I was unable to walk or stand. I was train-wrecked. My spine looked like the freeway after an earthquake… My mum put up a Christmas tree in my room and I remember saying to the tree, ‘I am not a cripple.’ They would come with cauldrons of hot flannel rags and pin them all over you – the heat was meant to do something to the muscles. In a very short space of time, I unfurled. They sent me home in a wheelchair, but I refused to use it. Polio survivors – Neil Young is another one – are a really stubborn bunch of people.”

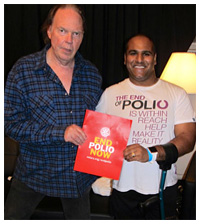

Image source: Rotary International

For 5-year-old Neil Young, “polio was the worst cold there is.” He contracted polio over the Labour Day weekend and was rushed 90 miles to Toronto through a thunderstorm in the back of the family station wagon, wearing a surgical mask and clutching a new toy train. “I didn’t die, did I?” was the first thing Neil said to his parents when they picked him up at the Hospital for Sick Children six days later. As Neil’s father, Scott Young, wrote, “It was years later before he told me he could still remember sitting in the hospital cot half upright, holding the sides to keep himself there because it hurt his back so much to lie down. But then he would fall asleep and let go, and when he fell back the pain would waken him again, crying.” By the time of his sixth birthday, Neil was a town celebrity: the first polio case to occur in Omemee. Another case of polio in a young boy had resulted in his death, but Young survived.

Image source: “24 Hours”, CBC News Winnipeg, 1988.

Yvonne Hudson was a 25-year-old mother and housewife when she fell victim to polio in Winnipeg, Manitoba in 1953 during Canada’s worst polio epidemic and one of the most severe ever seen. Like most cases, Yvonne’s polio experience started with a terrible headache and fever, followed the next day by a weak arm and more alarmingly, having trouble breathing and swallowing. Further complicating the experience, she was 8-months pregnant. She was admitted to the King George Isolation Hospital where her condition deteriorated and after five days she was put in an iron lung. She joined a large number of other victims of bulbar polio dependent on iron lungs; at the peak of the epidemic, there were 72 iron lungs operating at the same time. Some 15 hours after entering her iron lung, Yvonne gave birth to a healthy baby. She would spend six months in the iron lung before being weaned out of it. She then used a rocking bed for three months followed by specialized rehabilitation in the U.S.

Canada and “The Middle Class Plague”

Capturing the fear and mystery of polio during one of Canada’s first significant outbreaks in 1910.

Capturing the fear and mystery of polio during one of Canada’s first significant outbreaks in 1910.Image source: Toronto Star, August 17, 1910

The first significant outbreaks of polio struck in several parts of Canada in 1910. Though mostly infecting young children, newspaper reports indicated that the “strange epidemic” of infantile paralysis could also strike adults, often with deadly results. In 1916, the northeast United States was swept by an unprecedented polio epidemic, causing some 27,000 cases and 6,000 deaths. The epidemic soon spilled over the Canadian border, prompting the imposition of travel restrictions against U.S. visitors.

Image source: Public domain image

A new chapter in the history of polio began in 1921 when future U.S. President, Franklin D. Roosevelt, fell victim to “infantile paralysis” while vacationing in New Brunswick. His case sparked a transformation in how polio is publicly perceived, significantly broadening its apparent threat. In the early 1930s, to raise funds for medical research and support for polio victims, Roosevelt spearheaded the creation of the National Foundation for Infantile Paralysis and the launch of its annual “March of Dimes” fundraising campaigns. Inspired by the success of the NFIP, a Canadian Foundation for Poliomyelitis was established in 1948 and evolved into the March of Dimes Canada today.

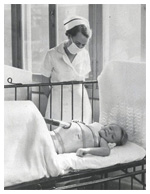

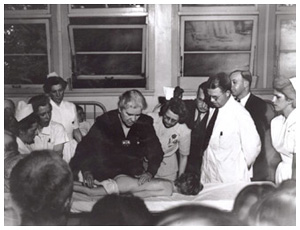

Polio patients, Hospital for Sick Children, Toronto, 1937

Polio patients, Hospital for Sick Children, Toronto, 1937Image source: Hospital Archives, The Hospital for Sick Children, Toronto (used with permission)

Between 1927 and 1932, a wave of increasingly alarming polio epidemics struck, in turn, British Columbia, Alberta, Manitoba, Ontario and Quebec, prompting provincial health departments to struggle with the management of the immediate threat, hospital treatment, and the long term physical and economic consequences.

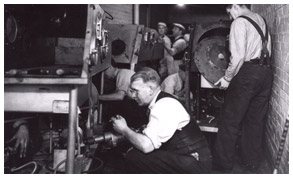

During the summer and fall of 1937, Ontario was hit with its worst ever polio epidemic, with over 2,500 reported cases and 119 deaths. In response, an experimental preventive nasal spray was tested, but proved fruitless. Also, the provincial government established a free polio treatment policy and sponsored the fabrication of 27 iron lungs in the basement of the Hospital for Sick Children. Though used primarily in Toronto, these “miraculous metal monsters” that enable paralyzed patients to breathe were shipped to other cities in the province, including Kingston.

Constructing iron lungs at the Hospital for Sick Children Toronto, 1937.

Constructing iron lungs at the Hospital for Sick Children Toronto, 1937.Image source: Hospital Archives, The Hospital for Sick Children, Toronto (used with permission)

Cover of The Horizon, newsletter of the Ontario Crippled Children’s Society, October 1937.

Cover of The Horizon, newsletter of the Ontario Crippled Children’s Society, October 1937.Image source: Hospital Archives, The Hospital for Sick Children, Toronto (used with permission)

Museum of Health Care, accession #997019003

The early 1940s witnessed a revolutionary approach to polio treatment and rehabilitation that was lead by Australian nurse, Sister Elizabeth Kenny. It was based on the use of “hot packs” and passive movement to re-educate affected muscles. The Kenny method represented a sharp move away from the older approach to polio treatment that was based on rest and keeping affected limbs immobile to prevent deformities and which also relied on orthopaedic surgery.

Canadian polio epidemics peaked in 1953 with almost 9,000 cases and 500 deaths nationally. The Canadian Air Force transported iron lungs across the country in a desperate attempt to meet the crisis. The western provinces were most severely affected and Manitoba was hit the hardest. In one Winnipeg hospital, 72 iron lungs operated at once at the peak of the epidemic, and when a thunderstorm knocked out power at an Edmonton hospital, nurses scrambled to manually pump each iron lung.

Inside the Iron Lung

"Inside the Iron Lung @ The Museum of Health Care, Kingston, ON"

Join medical historian/guest curator, Christopher Rutty, as he gives a tour of the iron lung built in 1937, which is the focal point of the original history of vaccines exhibit.

This archival film shows a demonstration of an iron lung in Los Angeles in the 1930s.

This video features a TV reporter in Washington, D.C. reporting about iron lungs from inside one in 1956.

Conquering the Crippler:

Canadian Polio Vaccine Innovations and Victories

National Foundation for Infantile Paralysis, March of Dimes, poster, 1940s

National Foundation for Infantile Paralysis, March of Dimes, poster, 1940sImage source: (public domain image)

The search for a vaccine to prevent the growing threat of polio was long and frustrating, constrained for decades by the limits of scientific understanding about the poliovirus and how it spread outside and inside the body. Although the poliovirus was first isolated in 1908, it could only be cultivated in a living host, and the only susceptible non-human host was monkeys.

There were few laboratories able to conduct polio research until the National Foundation for Infantile Paralysis (NFIP) was established in the U.S. in the late 1930s. The NFIP’s annual “March of Dimes” campaigns proved highly successful at generating funding to support polio research.

Beginning in the early 1940s, some of those dimes flowed north of the border to Connaught Medical Research Laboratories at the University of Toronto and helped fund a modest polio research effort that would grow significantly after World War II.

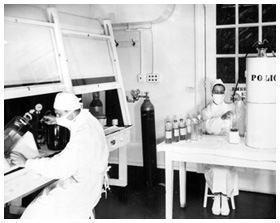

Dr. Leone Farrell and the “Toronto Method” of poliovirus cultivation, Connaught Laboratories, 1953-54

Dr. Leone Farrell and the “Toronto Method” of poliovirus cultivation, Connaught Laboratories, 1953-54Image source: Sanofi Pasteur Canada

In 1947, Connaught Laboratories launched a comprehensive poliovirus research program directed by Dr. Andrew J. Rhodes, a leading poliovirus specialist recruited from Great Britain. This work was supported with significant funding from the NFIP, as well as from Canadian life insurance companies and new Federal Public Health Research Grants,

1949 was a critical year on the road to a polio vaccine, most notably because: 1) the Nobel Prize winning discovery of how to grow poliovirus in test tubes using non-nervous tissues was made by researchers in Boston; and 2) a group of scientists at Connaught, led by Dr. Raymond Parker and Dr. Joseph Morgan, discovered “Medium 199,” which was the world’s first purely synthetic nutrient medium for growing cells.

Preparing poliovirus fluids in “Medium 199,” Connaught Laboratories, 1953-54.

Preparing poliovirus fluids in “Medium 199,” Connaught Laboratories, 1953-54.Image source: Sanofi Pasteur Canada

More critically, in 1952, Rhodes’ research team discovered that “Medium 199” worked ideally for growing poliovirus. This discovery sharply accelerated the work of Dr. Jonas Salk in Pittsburgh, who was convinced that a killed or inactivated poliovirus vaccine was possible and it could be now be safely tested on children.

In 1953, the next major problem in producing a polio vaccine was solved by a member of Connaught’s polio research team, Dr. Leone Farrell: how to make enough of it so that everyone could be immunized. Farrell developed the “Toronto Method” for cultivating the poliovirus in fluid cultures using large bottles gently rocked in custom built rocking machines.

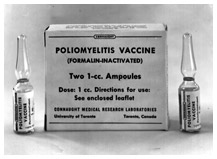

Salk Inactivate Polio Vaccine (IPV), Connaught Laboratories, 1956

Salk Inactivate Polio Vaccine (IPV), Connaught Laboratories, 1956Image source: Sanofi Pasteur Canada

By the spring of 1954, Connaught’s advancements made it possible for an unprecedented field trial of Salk’s polio vaccine in the U.S. and parts of Canada. In what Salk called a “Herculean task,” Connaught supplied all of the poliovirus fluids used to prepare the vaccine for the trial, which involved 1,800,000 “polio pioneers.”

On April 12, 1955, the much anticipated results of the Salk vaccine field trial were announced with unprecedented media attention: “It Works!” exclaimed the headlines. However, there was a setback when it was discovered that some batches of vaccine from one U.S. producer were not fully inactivated, leading to polio cases. While the U.S. launch of the Salk vaccine was suspended, after careful consideration, federal health minister, Paul Martin (himself a victim of polio, as was his son) decided that the Canadian launch of the vaccine, which was produced by Connaught Labs, should continue uninterrupted. Moreover, a detailed Canadian evaluation of the vaccine further demonstrated its safety and effectiveness.

This silent archival film was produced by Connaught Medical Research Laboratories in 1958 and illustrates how the Salk polio vaccine was originally prepared.

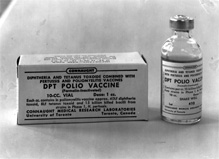

Combination Diphtheria-Pertussis-Tetanus-Polio (DPT-Polio) vaccine, Connaught Laboratories, 1959

Combination Diphtheria-Pertussis-Tetanus-Polio (DPT-Polio) vaccine, Connaught Laboratories, 1959Image source: Sanofi Pasteur Canada

Still, it took time for all age groups to be immunized and time for polio outbreaks to end. In particular, significant polio epidemics struck several parts of the country in 1958-59, primarily effecting un-immunized pre-school and older children, as well as adults. Beginning in 1959, the introduction of combined vaccines with polio vaccine added to the standard diphtheria-pertussis-tetanus and related boosters (DPT-Polio, DP-Polio, T-Polio) simplified and broadened publicly funded polio immunization programs in Canada.

Persistent polio incidence during the late 1950s highlighted the limits of the Salk inactivated vaccine. Also, limited supplies of the vaccine and growing polio incidence internationally pointed to the need for another type of polio vaccine that was cheaper to produce and could be easily given orally.

In 1962, with considerable Canadian involvement in research, development and careful evaluation, the Sabin oral polio vaccine (OPV) was launched. Several provinces and most of the United States soon switched to OPV, although the Salk vaccine was preferred in Ontario. By 1965, polio incidence in Canada had fallen to almost zero.

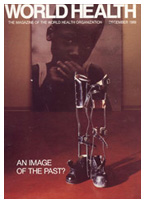

Progress of the global polio eradication program, 1988-2004.

Progress of the global polio eradication program, 1988-2004.Image source: World Health Organization

Although polio vaccines have been available, they were not always affordable or used effectively in many countries, leading to some 350,000 polio cases occurring each year worldwide in 1988. That year, the World Health Organization launched a global polio eradication program, hoping to repeat the success achieved in eradicating smallpox a decade earlier. However, polio would be a far more challenging disease to eradicate.

By the early 1990s, a new generation of enhanced potency Salk inactivated polio vaccine had been introduced in all provinces, replacing OPV. Wild poliovirus was officially declared eradicated in the Americas and it was no longer wise to continue to use OPV since it was a live virus vaccine and although carefully weakened, the virus could revert to virulence and cause the disease.

In 2014, and despite many past and present challenges, polio has been eradicated in most of the world, with the wild poliovirus endemic in only 3 countries: Nigeria, Afghanistan and Pakistan. However, local and regional political instability, particularly in the Middle East, has recently threated the gains made against polio, leading to its spread into countries where the disease had been eradicated.

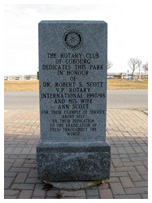

Dr. Robert S. Scott Park, Coburg, ON, dedicated to his work with Rotary International’s PolioPlus campaign.

Dr. Robert S. Scott Park, Coburg, ON, dedicated to his work with Rotary International’s PolioPlus campaign.(Photo by Felicity Pope)

The polio story is not over yet, and even when the wild poliovirus has finally been eradicated, the personal, physical, economic and political legacy of “The Crippler” will continue for those it directly and indirectly affected during the pre-vaccine era and those who continue to be stricken today.