Selling Sex: HRT and Knowledge Transmission in 1940s Ontario

Selling Sex

In my last post, I introduced my Margaret Angus Fellowship research for the summer. I’m going to be looking specifically at how doctors in Kingston used hormone replacement therapy (HRT) in the past and how they learned about hormones in medical schools like Queen’s. Normally, when people write about hormones, they focus on the history of discovering them or developing a new use for them in medicine. I’m more interested in how HRT became something local doctors learned about, were trained on in medical school, and prescribed to their patients.

Today, I’ll be showing you a bit more about how HRT became a part of Canadian doctors’ work in the early-to-mid twentieth century. To understand this, we’ll review a rare resource from within the Museum’s collections: a series of reference texts on sex hormones that covered how they could be used in medicine. These books were produced in Montreal and seem to have been sent directly to physicians by Schering, a drug manufacturer who produced crude extracts and synthesized hormones.

Spreading the Word

To introduce our evidence, these books were given to the Museum of Health Care by the Society of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists of Canada (SOGC). The set has three volumes (two volumes on estrogen and progesterone and one on testosterone). They were published in 1941 by Schering Ltd., a pharmaceutical manufacturer, and once belonged to a Dr. Dubé.

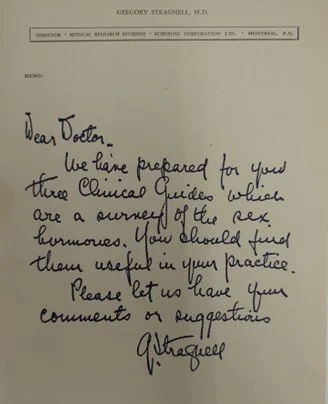

Schering was a prominent drug manufacturer for North Americans by the 1940s. They had offices and labs in Montreal to serve Canadian markets. They seem to have put significant effort into establishing a relationship with local labs and research teams. These clinical guides are interesting examples of how drug companies facilitated the spread of new therapies like HRT by making recent literature available to local physicians and making the hormones involved accessible for medical personnel. A memo from Gregory Stragnell, the Director of Schering’s Medical Research Division, was included with the books when they were sent to their owner. The note shows that companies compiled research and, arguably, advocated for these therapies’ relevance and importance in daily practice. Stragnell says as much to Dubé, writing: “We have prepared for you three clinical guides which are a survey of the sex hormones. You should find them useful in your practice. Please let us have your comments or suggestions.”[1]

Details on the owner of the books are scarce, but an obituary for a Dr. Jacques Dubé is included in a 1973 issue of the Canadian Medical Association Journal (CMAJ). It seems likely that he is the owner, given that he graduated from l’Université de Laval (Montreal) in 1943 and worked as a specialist surgeon in the small town of Notre-Dame-du-Lac (now part of the larger Témiscouata-sur-le-Lac municipality in Quebec). If this is the same Dr. Dubé, Schering could have sent them as a professional courtesy to a recent graduate, or he could have requested them for reference himself. Either way, this artifact demonstrates that Schering played a role in keeping doctors up-to-date on hormonal medicine and, arguably, marketed their own products as relevant and useful to them along the way. This was useful work to physicians at the time, as not all doctors had access to the latest research, but Schering nonetheless provided both the scientific publications and the materials for the emergent HRT practices in these cases.

Photograph of the Strathcona Medical Building Library at McGill University, c. 1920. For local students and doctors, keeping contact with university libraries and medical departments was a reliable way to access some of the most recent publications, research and ideas in medicine.

Photograph of the Université Laval’s Montreal campus, Rue Saint-Denis, c. 1900-1930. This was potentially the site of Dr. Dubé’s training and a source of clients for Schering’s services.

Let's Talk About Sex

The books’ foreword begins with a caveat: “The sex hormones have grown out of the troubled, early days of crude extracts, into the age of absolutely pure and precisely known principles of measurable high potency. They have been cleared of their mystical and imaginary powers, and have become accepted, rational, reliable treatment for specific indications.” [2] This statement is somewhat ironic considering that “estrogenic” cosmetics were being advertised for more than a decade after the texts were published (products we covered last time and are specifically called out as uncertain and “whimsical” by the guides).[3]

The books note that estrogen and progesterone, known contemporarily as "female" hormones, could be used for a variety of purposes. They could be helpful in alleviating menopause (when women stop having periods) and/or endometriosis (a condition where tissue grows outside the uterus). But they were also touted as a cure for “muscle strength, bodily vigor, mental acumen,” “sexual infantilism” or “incomplete sexual development,” and “certain nervous and metabolic disorders.”[4] Sexual “frigidity” (an elastic term that categorized a woman’s lack of interest in sexual activity as a medical problem) is also included as a natural site for the administration of “female” sex hormones. Several sections in the book focus on the sexual and behavioural conformity of patients with intersex or ambiguous sexual characteristics, encouraging physicians to look for “juvenile sexual attitude” among them and citing studies emphasizing how treatment could “augment the feminine appearance” while also leading to “an increase in sex consciousness with a corresponding change in emotional status” and “more stylish clothing and the use of cosmetics.”[5]

Photograph of Female Students at the McGill School of Physical Education, 1923. From the McGill University Archives, PR001133. A powerful association formed between appearance, behaviour and health in the first half of the twentieth century, particularly in the case of women.

For testosterone (or, as the books put it, “male sex hormone”) therapy, the texts begin with a history of the hormone’s synthesis, celebrating that “now, the pure, primary male sex hormone is available for therapeutic use, its potency exactly known and invariable and its chemical structure certain." [6]. The text emphasizes that “the development of a new and powerful therapy with the male sex hormone” between 1935 and 1941 stands as a “gratifying contrast to the presumed ‘cures’, imaginary or at best psychological, that have been reported for the past half-century.” [7] Once again, the text focuses on increased libido, vitality, hair growth, “self-confidence and other masculine traits” and genital size to match “the limits of normal variation”. [8] Tellingly, the text doubts “whether the actual male sex hormone constitutes a normal part of the female economy,” but admits that “it may be administered to produce certain temporary specific effects,” including care for uterine bleeding, after-pains, menstrual cramps and breast pains. [9]

The Schering reference texts show us a few important things about “sex hormone therapy” and its developing role in Canadian healthcare during the 1940s. As we will explore in future posts, hormones were embraced immediately by gynecology and obstetrics when it came to sex traits and sexual behaviour. Intersex bodies and people who did not conform to gendered expectations of behaviour were particularly targeted by early endocrinological advocates like Schering, who marketed hormones as a tool for facilitating sexual reassignment and encouraging gender conformity. These texts stand as an immediate example of how the divide between ‘normal’ and ‘pathological’ bodies –measured in terms of hormonal levels, genital size/shape and secondary sex characteristics— became more relevant and the logical subject of hormonal treatment through materials like these texts.

Special thanks to Ian M. Fraser and Janine M. Schweitzer for their generous support of the 2023 Margaret Angus Research Fellowship.

References

1 “Le docteur Jacques Dubé,” Canadian Journal of Medicine 109, no. 11 (1973): 1135.

2 Female Sex Hormone Therapy (Vol. 2), (Schering: Montreal, 1941): 4.

3 Female Sex Hormone Therapy (Vol. 2), 20

4 Female Sex Hormone Therapy (Vol. 2), 32-37.

5 Female Sex Hormone Therapy (Vol. 2), 42

6 Male Sex Hormone Therapy (Schering: Montreal, 1941), 9

7 Male Sex Hormone Therapy, 9

8 Male Sex Hormone Therapy, 29

9 Male Sex Hormone Therapy ,42-43.