MUSEUM BLOG

Globe and Mail: How lessons from the past can help shape future health outcomes

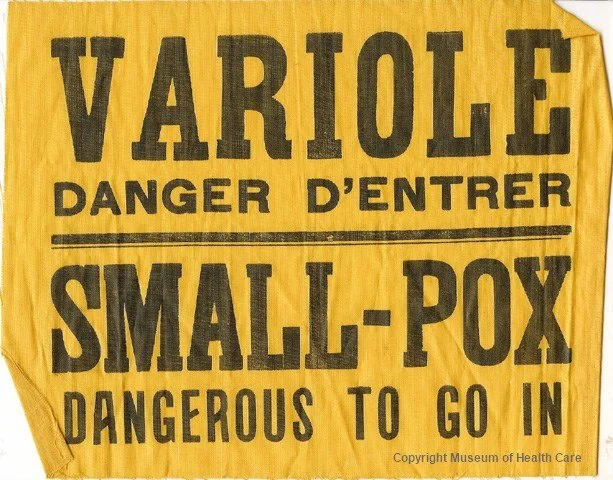

That’s where the Museum of Health Care aims to make a contribution. “Our objects can tell a million stories, not just about vaccines but also about vaccine hesitancy,” says Ms. McGowan. “A lot of the discussion that was the backlash against the smallpox vaccine, for example, is not that different from what you hear today. It is really interesting to see this continuity.” The question then becomes what lessons we are willing to learn, and Ms. McGowan believes that seeing an iron lung, a smallpox vaccination certificate or a poster about wearing a mask during the 1918-19 influenza epidemic can provide an extra incentive for seeking out valid evidence.

Smallpox – A Short History of Vaccination (Part 2)

Janet Parker was the last person in the world to die from smallpox in 1978. She was working as a scientific photographer above one of the labs at Birmingham Medical School. The lab was working with smallpox and Parker contracted the disease on August 11th. She would die a month later.This event shook the world not only because the last smallpox case in the UK was 5 years prior, but because smallpox was on its way to being confined to the history books.

The Spanish Flu at KGH: A Frequent and Quick Killer

The following data were obtained from the Admissions and Death Registers at Kingston General Hospital (KGH) for investigation during the research project. Within the Registers, cases of influenza were often associated with other diseases, most frequently pneumonia. If reference to ‘influenza’ was made in the patient’s Reason for Admittance, that individual was included in the cohort being studied. With such a high incidence of pneumonia developing from influenza during the Spanish flu, those with ‘pneumonia’ were also included in the cohort. However, because pneumonia may also develop from a myriad of conditions unrelated to the flu, diagnoses of ‘pneumonia and other non-influenzal disease’ were not included (e.g., anemia and pneumonia).

The Prophylactic Treatment of the Spanish Influenza

With the wide-sweeping devastation of the Spanish Influenza in the Fall of 1918, communities around the world were eager to come together and share insights and ideas about protective treatments and therapies.

The History of Vaccinations: The Build Up to the Spanish Flu

An understanding of disease resistance has existed in written records as far back as 429 BCE when the Greek historian Thucydides acknowledged that those who survived a smallpox epidemic in Athens were subsequently protected from the disease. Since a basic understanding of the biological underpinnings of infection was not understood for a long time, it was not until 900 AD when the Chinese developed a rudimentary smallpox inoculation. Chinese physicians noted how uninfected people who were exposed to a smallpox scab were less likely to acquire the disease or, if they did, that it was milder. The most common method of inoculation was to inhale crushed smallpox scabs through the nostrils.

Dr. Guilford B. Reed: The Influenza Vaccine That (sort of) Worked

Born in Port George, Nova Scotia in 1887, Dr. Guilford Bevil Reed grew up on the East coast as the son of the prominent ship builder and architect, William Reed. While living in the Annapolis Valley, Guilford developed a deep love of the natural world. He spent his days surrounded by five siblings and endless apple orchards, and maintained a curiosity that propelled him throughout his life.

From Variolation to Cowpox Vaccination: The First Steps Towards Eradicating Smallpox

Edward Jenner looms large in the history of vaccination. Known today as the “father of immunology,” Jenner is most famous for developing a vaccine against smallpox in the 1790s. The vaccine brilliantly made use of common knowledge. Milkmaids were known for having noticeably clear and smooth skin. They had, it seemed, managed to develop an immunity to smallpox by suffering (and surviving) a bout of the much milder cowpox.