The Public Life of Hormones: HRT in Ontarian Communities

Frederick Banting’s isolation of insulin in 1922 is a familiar touchstone for many Canadians. As an introduction to the history of hormones and medicine in the early twentieth century, Banting’s Nobel Prize-winning research has acquainted many of us with some of the impressive and unusual parts of the topic. The story has it all: extracting crude hormones from animal organs (dog pancreases), isolating the active hormone and trying to understand it well enough to use it in treatment. Banting’s work quickly became an example of scientific excellence at the time and continues to serve as a symbol of the role Canada could play in lifesaving, world-altering medicine today.

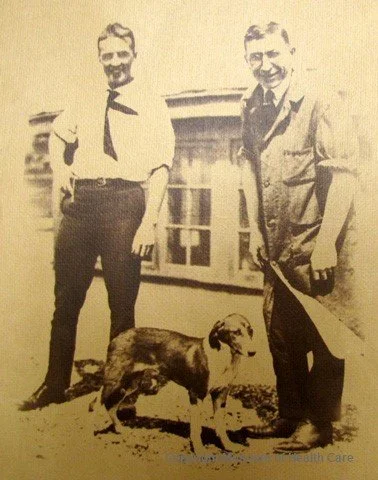

Figure 1: Print of Drs. Frederick Banting and Charles Best, and Dog 408. From the Collection of the Museum of Health Care at Kingston, 1971.5.50.

We can learn a lot from what we omit from this story, though. Banting was collaborating with his colleagues in the University of Toronto and throughout the world, rather than working in isolation. Beyond this, his research relied on a network of journals, drug manufacturers, physicians and public figures that made the discovery of insulin relevant beyond the confines of the lab. Ending the story with the discovery itself erases the larger history of how endocrinology captured the public’s imagination, drew corporate interest and came to be put into medical practice at the time. For people living in Canada at the start of the twentieth century, the isolation of insulin was a convincing and instructive example of hormones’ potential to shape the body, as well as a glimmer of hope for treating diseases previously outside of our control.

Even at the local level, Banting and co.’s work seems to have been a watershed for public interest in hormones. Ontarian papers like the Kingston Whig-Standard, Windsor Star and North Bay Nugget began to report on hormones more frequently in the 1920s. Articles appeared under headlines like “Pharmaceutical Manufacturing a Huge Business,” and “Pituitary Gland Sets Character.” Many of these articles wrote about endocrinology as a revolutionary –and lucrative— direction for medical science and the province’s economy.[2] Drug manufacturing plants in Walkerville (now Windsor), Brockville, Montreal, and Toronto were celebrated as sources of prestige and prosperity for their communities.[3]

Postcard of the Parke Davis & Company Office and Laboratory Buildings in Walkerville, ON (now Windsor), 1927. From the Collection of the Southwestern Ontario Digital Archive, Mike Skreptak Collection; Box 1, R-77458. https://swoda.uwindsor.ca/node/2493 [4]

As hormones like insulin, pituitrin, estrogen and testosterone became more reliably available in the province, doctors would begin prescribing them in their own day-to-day practice as well. As this area of medicine became more well-known, patients would begin seeking out hormonal replacement therapies (HRT) for a variety of different reasons – contraception, weight loss, bodybuilding and gender-affirmation chief among them. Surveying local paper coverage shows us, then, a trace of the public life of hormones: people gradually came to know about, care about, and incorporate hormones into their healthcare. I believe that we don’t know enough about how this actually happened at the local level. A medical niche was carved out for hormonal treatments after scientific discoveries, but how did physicians and their patients become aware of them and convinced of their potential? HRT emerged as a therapeutic option, but how was it actually explained, made available and put into practice? Did these circumstances play a role in making HRT available for some Canadians over others?

My project for this summer’s Margaret Angus Research Fellowship will try to unearth some of this history, looking at hormones’ incorporation into physicians’ education, hospitals, and peoples’ daily lives. By investigating the education of physicians at Queen’s medical school, records of their practice and training, news sources like the ones considered here, and 2SLGBTQI+ community records and ephemera, I will be looking into the local history of HRT in Kingston and Ontario more generally.

Public(izing) Sex

Although insulin and other advances in glandular research are an important part of this history, I am particularly interested in public awareness of the “sex” hormones in Kingston and their role in HRT’s public life. Beyond the fact that 2SLGBTQI+ medical history is my research background, I think that understanding how hormones changed public worldviews and medical practices about sex is an important contribution to make to Canadian history in general. My hope is that, by establishing some local history, I can provide better information for debates on how “experimental" HRT-based gender-affirmation practices are today. By focusing on public and professional awareness of hormonal medicine, I want to develop a better image of how gender-affirming endocrinology emerged in Canada: who it was for, who it might have helped or harmed, and how transgender, intersex and genderqueer people in Kingston have approached it over time.

Testosterone, estrogen and progesterone were recognized to affect menstruation, hair growth/loss and sexual characteristics as early as 1927.[7] Throughout the 1930s and 1940s, these chemical messengers would be synthesized and incorporated into treatments oriented towards matching one’s body and behaviour to social expectations of what a man or woman should be or do. This association of sexual characteristics with particular hormones would also become a part of the Canadian public’s worldview as well, rather than being limited to specialist knowledge. Estrogen, particularly, found early purchase in the local cosmetics industry. By analyzing the newspaper debates surrounding hormonal cosmetics, we can see an early example of how the association of hormones with particular sexes was built up over decades of science and journalism.

A short article in the Kingston Whig-Standard notably criticizes women of the time “fighting time with chemical warfare,” noting hormonal creams and oils as a particular example of modern excess. The 1935 editorial claims that readers’ grandparents had no use for these products, that “no suitor of lace valentine days would have sent his mistress a jar of turtle glands…Only in late years has public improvement before a mirror become anything but confession to a bad complexion and bringing up.”[8]

As an example of these kinds of products’ availability and “feminizing” effects, an ad for Helena Rubinstein’s “Estrogenic Hormone Twins” appears in the St. Catherine’s Standard on January 5, 1949. The cream and oil would supposedly “work wonders while you sleep, smoothing away fine lines and wrinkles,” while acting as “an invisible beauty treatment,” by day.

We now understand that androgens (testosterones), estrogens and the other steroids effecting genital development, hair growth and other sexual characteristics are not specific to one type of body over another. Human bodies of all kinds deploy these hormones to various effects at different stages of life, but particular ideas about male/female difference were assigned to them early on in their history. Historians have attributed the gendering of these hormones to different causes, but most agree that the eugenics movement’s interest in reproduction and “deviant” behaviour were major factors in this interpretation being so common in the early twentieth century.[11] As a result of this focus, intersex children, 2SLGBTQ+ people and women were at times compelled into treatment designed to ensure bodily/psychological conformity to these expectations –something we’ll explore more in later posts.

Special thanks to Ian M. Fraser and Janine M. Schweitzer for their generous support of the fellowship this year.

References

[1] Print of Drs. Frederick Banting and Charles Best, and Dog 408. From the Collection of the Museum of Health Care at Kingston, 1971.5.50

[2] “Million-Dollar Obligation to Canada’s Health Needs,” The National Post (Toronto, ON), September 15, 1956, p. 34; See also: “Quality Control Boosts Cost of Drugs,” The National Post (Toronto, ON), June 11, 1960, p.55; “Drug Research to Increase in Canada,” The National Post (Toronto, ON), June 6, 1964.

[3] “Pharmaceutical Manufacturing is Huge Business: Owner Needs a Farm, Well Stocked, as Well as a Factory,” The Windsor Star (Windsor, ON), March 10, 1937, p.16. See also: “Third Hormone Maiy (sic) Be Aid for Arthritis,” Niagara Falls Review (Niagara Falls, ON), December 28, 1950, p.3.

[4] Postcard of the Parke Davis & Company Office and Laboratory Buildings in Walkerville, ON (now Windsor), 1927. From the Collection of the Southwestern Ontario Digital Archive, Mike Skreptak Collection; Box 1, R-77458. https://swoda.uwindsor.ca/node/2493.

[5] Photograph of Mr. Pete Corbett working at the Parke Davis & Company manufacturing plant in Brockville, c. 1965. From the Collection of the Brockville Museum, 004.PA030.001.004.

[6] Stamp commemorating the discovery of insulin, issued in 1976. From the Collection of the Museum of Health Care at Kingston, 1979.19.1

[7] Nelly Oudshoorn, Beyond the Natural Body: An Archaeology of Sex Hormones (London: Routledge, 1994): 26-28.

[8] The Kingston Whig-Standard (Kingston, Ontario, Canada) Jan. 25, 1935: p. 6.

[9] The Kingston Whig-Standard (Kingston, Ontario, Canada) Jan. 25, 1935: p. 6.

[10] MacQuillen’s Drugs, “Helena Rubinstein: Estrogenic Hormone Twins,” The Standard (St. Catherines, ON) January 5, 1949.

[11] Diedrik F. Janssen, “Endocrinology’s Early Historians (1889-1914) and the Forgotten Prehistory of Testosterone,” Sexual Medicine Reviews 12 (2024): 192-198. See also: Jennifer Terry, “Anxious Slippages Between ‘Us’ and ‘Them’: A Brief History of the Scientific Search for Homosexual Bodies,“ in Deviant Bodies: Critical Perspectives on Difference in Science and Popular Culture (Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, 1995): 129-169.

About the Author

Matt Edwards (he/they) is a PhD Candidate in Tri-University History program. He holds a Master’s in History from Carleton University, Ottawa, and has previously worked within the NGO and heritage sectors as a coordinator, program interpreter and educator. Matthew’s doctoral research documents the history of conversion therapy in the Canadian healthcare system, looking specifically at its presence within medical school curricula and clinical training in central Canada during the 20th century. Their research interests include the history of mental healthcare, gender, sexuality and education.