Diphtheria

“The Strangler”

Image source: Sanofi Pasteur Canada

Characterized as “The Strangling Angel of Children,” diphtheria is a bacterial infection caused by Corynebacterium diphtheria, transmitted through close contact with an infected individual, usually via respiratory secretions spread through the air. Some people can be chronic carriers without knowing it.

As the disease advances, the toxin produced by the bacteria causes a thick film to develop in the throat that makes it increasingly difficult to breathe, ultimately strangling the patient to death in many cases. The spread of the toxin in the body can also seriously affect the heart and other vital systems. Untreated, diphtheria fatality rates range between 5% and 10%, and in children under 5 and adults over 40, can be as high as 20%.

Medical reports of a deadly “strangulation” disease first appeared in the early 1600s, emerging as a greater threat with the growth of cities and easier person-to-person spread. The disease was not given its official name until 1826 – diphtérite - derived from the Greek word for “leather” or “hide,” which describes the distinctive coating that appears in the throat of its victims.

The diphtheria threat grew significantly during the late 19th century to become one of the major causes of death, fuelled by the industrial revolution and increasingly crowded urban centres. Though mostly a disease associated with the poor and a particular threat to children, diphtheria did not discriminate by class and age, and its cause, route of spread and cure remained a mystery until the last part of the 19th century.

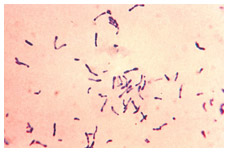

Public health statistics in Ontario, 1880. Note number of diphtheria deaths.

Public health statistics in Ontario, 1880. Note number of diphtheria deaths.Image source: Canada Health Journal, Feb. 1881

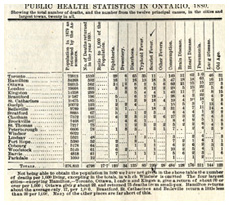

Dr. Humphrey’s Specific #34; a patent medicine used fortreating diphtheria, 1881.

Dr. Humphrey’s Specific #34; a patent medicine used fortreating diphtheria, 1881.Image source: Museum of Health Care, accession #996001624.

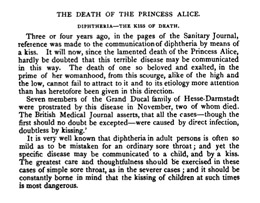

“The Kiss of Death”

Underscoring diphtheria’s broad threat was the dramatic experience of Princess Alice, daughter of Queen Victoria, who succumbed to diphtheria in 1878 at age 35. Alice fell ill after 4 of her 7 children, and her husband, the Grand Duke of Hesse-Darmstadt, were stricken by the disease, although it was fatal in only their youngest child. However, none of the other 60 members of the Grand Ducal household were affected. It was thought that the disease could be spread though the innocent kiss between a mother and child, neither showing symptoms more serious than a sore throat, yet a “kiss of death” harbouring and unknowingly spreading “the strangler.”

Image source: Wikipedia (public domain image)

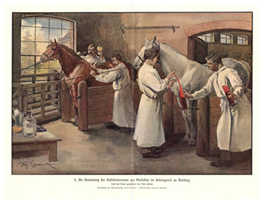

Preparing diphtheria antitoxin from the white blood cells of horses, Marburg, Germany, c. 1895.

Preparing diphtheria antitoxin from the white blood cells of horses, Marburg, Germany, c. 1895.Image source: Images from the History of Medicine, U.S. National Library of Medicine (public domain image)

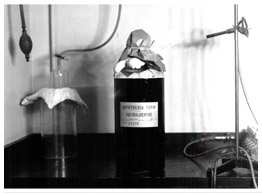

The diphtheria bacterium was first identified in the 1880s and in the 1890s diphtheria antitoxin was developed in Germany to treat victims of the disease. The antitoxin is prepared after horses are injected with increasingly large doses of diphtheria toxin. The toxin does no harm to the horse, but stimulates an immune response and the white blood cells can be processed into antitoxin. If given in time and in large enough doses, antitoxin could save lives, but it did not prevent diphtheria, nor stop it from spreading.

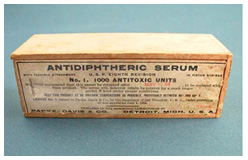

Diphtheria Antitoxin (Park, Davis & Co.),1908.

Diphtheria Antitoxin (Park, Davis & Co.),1908.Image source: Museum of Health Care, accession #997001096

A physician who practised before antitoxin was generally available, vividly describes how devastating diphtheria could be:

Diphtheria Antitoxin (Park, Davis & Co.), 1901.

Diphtheria Antitoxin (Park, Davis & Co.), 1901.Image source: Museum of Health Care, accession #000001080

“I recall the case of a beautiful girl of five or six years, the fourth child in a farmer’s family to become the victim of diphtheria. She literally choked to death, remaining conscious till the last moment of life. Knowing the utter futility of the various methods which had been tried to get rid of the membrane in diphtheria or to combat the morbid condition, due, as we know now to the toxin, I felt as did every physician of that day, as if my hands were literally tied and I watched the death of that beautiful child feeling absolutely helpless to be of any assistance.” (“Diphtheria: A Popular Health Article,” The Public Health Journal 18 (Dec. 1927): 574

Diphtheria antitoxin information post card,1907.

Diphtheria antitoxin information post card,1907.Image source: Museum of Health Care, accession #996001584

Ensuring diphtheria antitoxin was available and affordable to those most vulnerable to the disease remained a challenge. This sometimes prompted heroic efforts to get antitoxin to where it was urgently needed. Among the most famous such efforts was the 1065 km “Great Race of Mercy” dog sled journey in 1925 to bring antitoxin to Nome, Alaska. There was also the 2000 km mid-winter “mercy flight” in January 1929 between Edmonton and Fort Vermillion, Alberta to deliver antitoxin in the face of an outbreak. There were also heartbreaking decisions for parents and doctors, faced with a limited supply of antitoxin, to choose which sick child should get it.

Canada and “The Strangler”

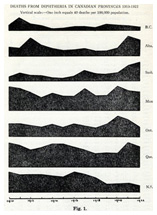

In 1924, there were 9,000 diphtheria cases reported in Canada, the highest ever, and it remained the number one cause of death of children under 14 until the mid-1920s, killing some 2,000 each year despite the availability of diphtheria antitoxin.

Until 1914, diphtheria antitoxin had to be imported into Canada at prices often beyond the means of families most vulnerable to the disease. This situation prompted the establishment of the Antitoxin Laboratory at the University of Toronto in May 1914. The Lab was pioneered by the unique vision of Dr. John G. FitzGerald to be a self-supporting source of not only antitoxin, but also other essential public health products, including rabies and smallpox vaccine, produced as a public service for free distribution through provincial health departments. In 1917 this unique institution would expand and become known as Connaught Laboratories.

Canada’s first diphtheria antitoxin supply was produced in this backyard stable in Toronto in 1913-14, forerunner of Connaught Laboratories.

Canada’s first diphtheria antitoxin supply was produced in this backyard stable in Toronto in 1913-14, forerunner of Connaught Laboratories.Image source: Sanofi Pasteur Canada

Despite the broader availability of diphtheria antitoxin in Canada, the disease remained a major public health threat until the introduction of a preventive vaccine known as “diphtheria toxoid” during the late 1920s.

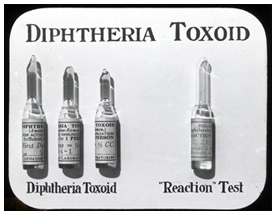

In 1923, Gaston Ramon, at the Pasteur Institute in Paris, France, discovered that when diphtheria toxin was exposed to minute quantities of formaldehyde and heated, the toxin became non-toxic, yet could stimulate active immunity like a vaccine. Ramon was able to test diphtheria toxoid and demonstrate its antigenic value, but only on a small scale.

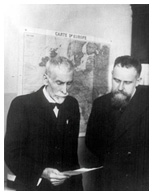

Early in 1924, Dr. FitzGerald visited Ramon and was very impressed with the potential of the new toxoid to finally bring diphtheria under control. He was confident that Connaught Labs could prepare the toxoid on a large enough scale to enable a series of substantive field trials in Canada to definitively test its preventive power. Wasting little time and while still at Ramon’s lab in Paris, FitzGerald sent a message back to Connaught asking Dr. Peter Moloney, the Lab’s expert on diphtheria toxin, to immediately start preparing the toxoid. Moloney’s subsequent development of the "Moloney Reaction Test" (an intradermal allergy test) ensured that the vaccine could be administered safely.

This silent home movie from the late 1920s, documents a visit to the Pasteur Institute in France by a scientist from Connaught Laboratories. It highlights the origin of the Institute after the discovery of the Pasteur Rabies Vaccine Treatment, and then illustrates the production of diphtheria antitoxin and diphtheria toxoid.

Image source: Sanofi Pasteur Canada

“Slaying the Dragon” - Canadian Diphtheria Toxoid Trials

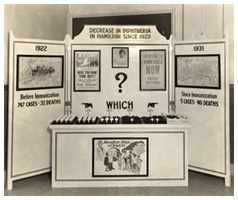

After preliminary studies, by October 1925 the new toxoid was ready to be given to children in six provinces, primarily in Ontario, where a total of 15,000 Brantford, Windsor and Hamilton children were given two doses. The results in Hamilton were particularly significant, the toxoid bringing diphtheria incidence and deaths down very sharply. FitzGerald’s team focused next on Toronto with a more sophisticated evaluation of the toxoid. Some 36,000 children were involved in this carefully controlled study between 1926 and 1929, which conclusively proved that the toxoid reduced diphtheria incidence by at least 90% among those given three doses.

This rate of effectiveness was maintained in Toronto and elsewhere into the 1930s, but the Americans and British were not yet as enthusiastic. The Canadian results were not well known outside of the country until FitzGerald and others from Connaught presented them personally. Moloney’s “reaction test” eased most American concerns by the mid-1930s, but the British resisted introducing the toxoid until World War II. However, by the early 1940s the British billboards boldly stressed the possibilities of diphtheria toxoid: “If Canada can do it, why can’t we?”

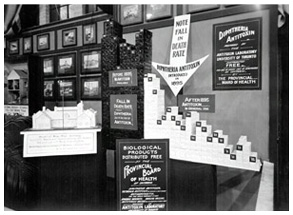

Slaying the diphtheria dragon, Hamilton public health exhibit, 1931

Slaying the diphtheria dragon, Hamilton public health exhibit, 1931Image source: Sanofi Pasteur Canada

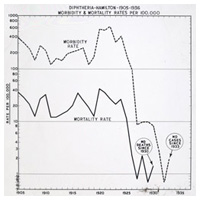

Diphtheria incidence in Hamilton, 1905-1936, and the impact of diphtheria toxoid.

Diphtheria incidence in Hamilton, 1905-1936, and the impact of diphtheria toxoid.Image source: Sanofi Pasteur Canada

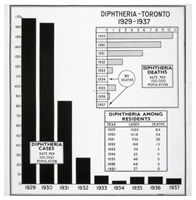

Diphtheria in Toronto, 1929-1937 and the impact of diphtheria toxoid.

Diphtheria in Toronto, 1929-1937 and the impact of diphtheria toxoid.Image source: Sanofi Pasteur Canada

Promoting diphtheria immunization, United Kingdom government, 1940s.

Promoting diphtheria immunization, United Kingdom government, 1940s.Image source: Wikipedia/ UK government (public domain image)

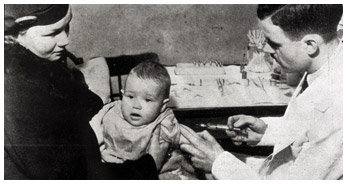

Diphtheria toxoid was the first modern vaccine, the first paediatric vaccine, and provided the foundation of public health immunization programs in Canada and elsewhere. Diphtheria remains a very rare disease in Canada thanks to the routine use of diphtheria toxoid, most often as part of paediatric combination vaccines and booster shots for adolescents and adults.

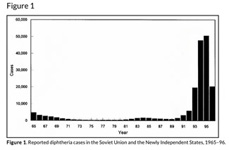

After the break-up of the former Soviet Union in the late 1980s, very low vaccination rates lead to an explosion of diphtheria cases in the early 1990s, mostly among adults who had not been adequately immunized. Diphtheria still exists in many parts of the world and without population-wide vaccination programs it could easily come back to Canada.

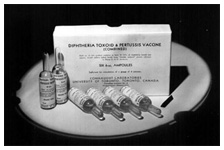

Diphtheria Toxoid – Pertussis Vaccine (DP), Connaught Laboratories, 1940s.

Diphtheria Toxoid – Pertussis Vaccine (DP), Connaught Laboratories, 1940s.Image source: Sanofi Pasteur Canada

Diphtheria-Tetanus-Pertussis combined vaccine, Park, Davis & Co., 1956.

Diphtheria-Tetanus-Pertussis combined vaccine, Park, Davis & Co., 1956.Image source: Museum of Health Care, accession #000001472

Pentacel® combined vaccine that protects against diphtheria, pertussis, tetanus, polio and Hib, 2006.

Pentacel® combined vaccine that protects against diphtheria, pertussis, tetanus, polio and Hib, 2006.Image source: Sanofi Pasteur Canada

Diphtheria incidence, Soviet Union/ Newly Independent States, 1965-1996.

Diphtheria incidence, Soviet Union/ Newly Independent States, 1965-1996.Image source: Emerging Infectious Diseases, Dec.1998 (public domain image)