Pertussis

Persistent Pertussis

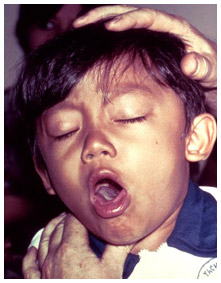

Pertussis is a stubborn respiratory disease caused by the Bordetella pertussis bacterium. It is better known as “whooping cough” because of the deep “whooping” sound it causes. Pertussis affects people of all ages, although it is of most concern among very young children.

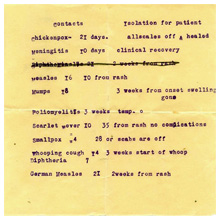

Image source: Wikipedia/ CDC (public domain image)

At the turn of the 20th century, pertussis killed 5 out of every 1000 children before their fifth birthday, mostly infants younger than 12 months of age. Severe cases, especially among infants too young to be immunized, can lead to permanent lung damage, hernias, brain damage, blindness, and sometimes death.

Pertussis begins much like any other respiratory infection, but soon the most serious stage of the disease - the “100 day cough”- starts, marked by coughing fits that can last for several minutes. In young children especially, the severity and frequency of coughing means that they become out of breath and may vomit, faint or have a seizure.

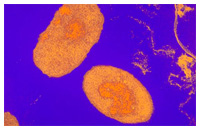

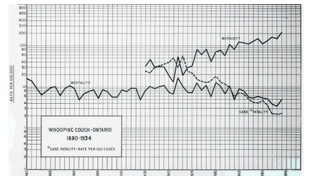

Before the first effective pertussis vaccine became available in Canada in the late 1930s, pertussis case incidence rates reached some 156 per 100,000 nationally in most years, reaching a peak of over 19,878 cases in 1940 (or 175 cases per 100,000). Today, the number of cases each year in Canada ranges between 1,000 and 3,000.

In Ontario, there were 214 deaths in the province in 1907 officially attributed to whooping cough, 141 of which involved children less than 1 year of age. However, there was considerable under-reporting of the disease, as one Toronto physician stressed in a 1915 Public Health Journal article. He was “anxious to put the question of Whooping Cough in its full light, so that something definite may be done, and done soon, to correct a condition of affairs which is, so say the least, deplorable.” This was particularly true in Toronto, where “practically nothing” was being done “to control this terrible disease.” It was a reportable disease, “but there is no doubt that very few of the cases are reported. They are constantly turning up at the Out-Patient Department of the Hospital for Sick Children and in this way they infect hundreds of other children before the disease is diagnosed.”

In Ontario, pertussis epidemics were most severe in 1906 (1,076 cases and 240 deaths), 1912 (1,414 cases and 419 deaths), 1925 (3,827 cases and 273 deaths), 1929 (4,897 cases and 194 deaths) and the worst in 1936 (7,890 cases and 112 deaths) just before a new pertussis vaccine was introduced. While the numbers of pertussis cases fell to lower levels by the 1940s, the numbers of deaths due to pertussis in Canada fell to almost zero by the late 1950s.

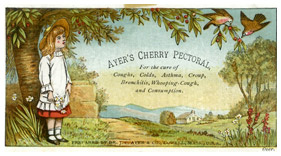

Ayer’s Cherry Pectoral patent medicine, which would “cure” whooping cough, c. 1870-1906

Ayer’s Cherry Pectoral patent medicine, which would “cure” whooping cough, c. 1870-1906Museum of Health Care, accession #1977.12.218

Personal Perspectives on Pertussis

Humphrey’s Homeopathic No. 20, treatment for whooping cough, c. 1890s

Humphrey’s Homeopathic No. 20, treatment for whooping cough, c. 1890sMuseum of Health Care, accession #1980.18-160

As the most susceptible to the severest effects of pertussis are infants and very young children, gaining a first person personal perspective of the experience of this disease is difficult. However, physicians who encountered whooping cough all too frequently before an effective vaccine brought the disease under control, can provide some poignant perspective on how it was experienced, as Dr. R. Cameron Stewart did in the March 1938 issue of The Canadian Nurse:

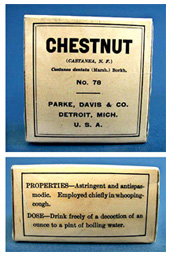

“Chestnut” over-the-counter treatment, employed chiefly in whooping cough, Park, Davis, c. 1930s

“Chestnut” over-the-counter treatment, employed chiefly in whooping cough, Park, Davis, c. 1930sMuseum of Health Care, accession #000001016

“An attack of whooping cough is an ordeal for the patient and also for his family. The coughing, whooping and vomiting, recurring all too frequently, are disturbing and messy episodes to everyone within sight or hearing. The unavoidably long period of quarantine involves much loss of time for school children and for adults employed outside the home. Lacking any means of prophylaxis easily applied and of proved efficacy, control of epidemics is a difficult problem for the public health authorities and those in charge of children’s institutions. Medical treatment is tedious, often expensive, and usually not particularly satisfactory. The well-being of the patient rests largely with the nurse.”

A further perspective on the family impact of pertussis during this period can be gained through the lens of a newspaper reporter. Greg Clark is a Toronto Star reporter who, in a December 13, 1934 story in support of the “Star Santa Clause Fund” profiled an unlucky family during the Depression with an 18-month old child stricken with whooping cough.

“Whooping cough, as you know, takes its time. It starts with one and a week later, it takes on another. The 18-months-old baby has it now. He is old enough to be toddling. He doesn’t want to stay in bed all day. He is full of ginger. But every little while, and especially about midnight or two o’clock in the morning, he is ripped and racked and torn by incredible storms of coughing and of pain; and everyone is awake and terrified in the night.”

Video of a young boy showing the distinctive sound of whooping cough. Source: CDC

A further perspective on the personal experience of pertussis through the eyes of adolescents and adults is provided in this video, “Pertussis in Adults and Adolescents,” Pasteur Mérieux Connaught, 1999

Early Battles Against Pertussis

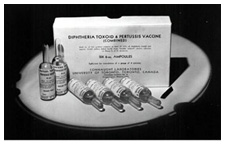

Image source: Sanofi Pasteur Canada

Guillaume De Baillou (1538-1616) was the first to formally describe a disease very much like whooping cough after an epidemic in Paris in 1578. He referred to this distinctive disease as “quinte,” but it was also known variously as “dog bark” in Italy, “chin cough” or “kin cough” in England and the “100 day cough” in China. It was not until 1679 that Thomas Sydenham first gave this disease the scientific Latin name, “infantum pertussis,” to formally describe a thorough or violent (“per”) cough (“tussis”) of any kind.

Image source: Sanofi Pasteur Canada

More than two centuries would pass before the infection-causing bacterium was first identified. In 1900, the team of Jules Bordet (1870-1961) and Octave Gengou (1875-1957) at the Pasteur Institute in Brussels discovered the cause of pertussis after isolating a bacterium they later called Bordetella pertussis. In 1906, they were able to cultivate B. pertussis from a sputum sample collected from Bordet’s five-month-old daughter suffering from whooping cough using a solid artificial media. Gengou also isolated B. pertussis from his young son.

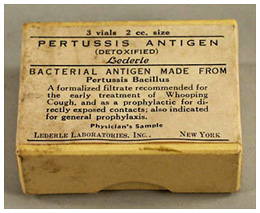

Gengou was a Belgian bacteriologist who went on to develop the first pertussis vaccine in 1912, based on killed B. pertussis bacteria. By 1914, whooping cough vaccines for prevention, but particularly for treatment of active cases, were prepared by several labs in Europe and the U.S. using stock or standard strains of B. pertussis, although establishing their value was a challenge.

A Canadian supply of pertussis vaccine was first prepared in 1919 by the Ontario Provincial Laboratory and then Connaught Laboratories began producing it in the early 1920s. However, by this time a “fresh” approach to developing a more effective pertussis vaccine was emerging. This approach was based on a better understanding of the four phases in the natural history of the B. pertussis bacteria and the importance of using fresh “phase 1” strains of the bacteria for a vaccine, rather than standardized older and weaker supplies.

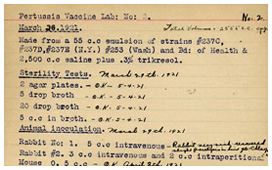

Pertussis vaccine production record, Connaught Laboratories, March 1921. Note the standard strains used.

Pertussis vaccine production record, Connaught Laboratories, March 1921. Note the standard strains used.Image source: Sanofi Pasteur Canada

Preparing a Fresher Generation of Pertussis Vaccine

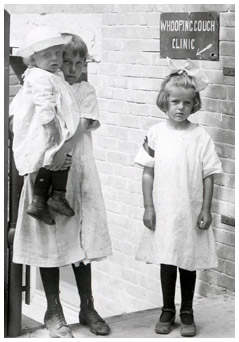

Children at the Whooping Cough Clinic, Hospital for Sick Children, Toronto, 1930s.

Children at the Whooping Cough Clinic, Hospital for Sick Children, Toronto, 1930s.Image source: Sanofi Pasteur Canada

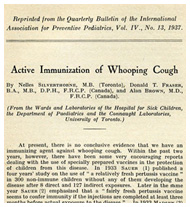

During the mid-1930s, inspired by renewed international pertussis research, scientists at Connaught Laboratories, led by Dr. Nelles Silverthorne, a paediatrician based at the Hospital for Sick Children, worked to prepare and test a more effective pertussis vaccine. Operating in a “Whooping Cough Clinic,” Silverthorne focused on collecting fresh strains of the bacteria on cough plates from actual whooping cough cases and then cultivating and carefully inactivating these cells to prepare a vaccine. After conducting a series of small clinical trials in the Toronto area, by early 1937 Connaught began distributing the new pertussis vaccine, although supplies were limited due to the laborious production process.

Seminal article by N. Silverthorne, D.T. Fraser and A. Brown, describing whooping cough vaccine progress by Connaught Laboratories and the Hospital for Sick Children, 1937.

Seminal article by N. Silverthorne, D.T. Fraser and A. Brown, describing whooping cough vaccine progress by Connaught Laboratories and the Hospital for Sick Children, 1937.Image source: Sanofi Pasteur Canada

In the early 1940s, in a quest to develop a more efficient method for pertussis vaccine production at Connaught, Dr. Robert J. Wilson began experiments based on a new fluid culture medium, while Drs. Leone Farrell and Edith Taylor focused on developing larger scale production methods, such as using a rocking bottle machine. In the early 1950s, Dr. Farrell would further adapt this method to make Salk polio vaccine production possible.

By the early 1940s, while pertussis vaccine became more widely distributed, its use created a new challenge – an extra course of childhood needles. Thus, Dr. Robert J. Wilson spearheaded work on a DP vaccine, which combined pertussis vaccine with the well-established diphtheria toxoid to protect children against both diseases at the same time. By the mid-1940s, simultaneous protection against tetanus was also possible with DPT. Similarly, after the introduction of the first polio vaccine in 1955, Connaught took the global lead in developing a new generation of combined vaccines, known as DPT-Polio, DT-Polio and T-Polio, which were launched in 1959.

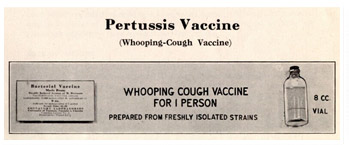

Pertussis vaccine (fresh strain), Connaught Laboratories, c. 1938

Pertussis vaccine (fresh strain), Connaught Laboratories, c. 1938Image source: Sanofi Pasteur Canada

Canada and Modern Pertussis Vaccines

During the 1970s, after several improvements in the production of the fresh strain, or “whole cell” vaccine, concerns persisted about a possible connection between the pertussis vaccine and rare adverse reactions. Some parents declined to have their children immunized against pertussis, and some countries, such as Sweden and Japan, scaled back or suspended their pertussis immunization programs, inevitably resulting in significant spikes in pertussis incidence.

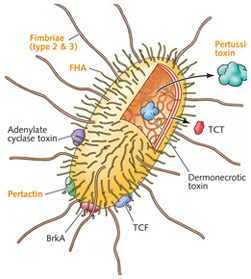

While scientific studies could not establish a direct connection between such reactions and the vaccine, during the 1980s, researchers, including at Connaught Laboratories, focused on developing a less potentially reactive and more effective “acellular” pertussis vaccine. It would be prepared from only the key components of the bacteria necessary to stimulate immunity.

Diagram of Bordetella pertussis organism, highlighting the five most important antigenic components used for vaccine production, 1990s.

Diagram of Bordetella pertussis organism, highlighting the five most important antigenic components used for vaccine production, 1990s.Image source: Sanofi Pasteur Canada

Component Pertussis Vaccine production facilities, Sanofi Pasteur Canada, Toronto, c. 2006.

Component Pertussis Vaccine production facilities, Sanofi Pasteur Canada, Toronto, c. 2006.Image source: Sanofi Pasteur Canada

A team of researchers at Connaught first focused on isolating the pertussis toxin, the primary antigenic component of the B. pertussis bacterium. This team next developed methods to isolate four additional critical components of the bacterium. They also pioneered a more efficient method for final chemical detoxification of these components, which were then standardized and expanded for large-scale production.

Image source: Sanofi Pasteur Canada

In 1996, after extensive clinical trials in several countries, Connaught’s 5-component pertussis vaccine was licensed in Canada and soon exported globally. Connaught’s was among several similar acellular vaccines produced by vaccine companies, which were primarily administered in a variety of combination forms, such as Pentacel®, which simultaneously prevents diphtheria, tetanus, polio, Hib (haemophilus influenza b) and pertussis.

However, even with the new generation of pertussis vaccine, many still suffer from pertussis and there are periodic outbreaks of the disease in Canada and elsewhere. World wide, whooping cough still affects 48.5 million people yearly, resulting in nearly 295,000 deaths. Significant sources of increased incidence in recent years have been adolescents and adults. Pertussis immunity from childhood vaccinations fades over time, thus leaving older people vulnerable to pertussis infections. And while the disease is not as dangerous to adolescent and adults, they can easily transmit it to un-immunized, or incompletely immunized, young children and infants. Combined vaccines, such as ADACEL®, boost tetanus, diphtheria and pertussis immunity in adolescents and adults and provide indirect protection to the very young, who are most vulnerable to the worst effects of the disease.