Smallpox

“The Speckled Monster”

Image Source: Wikipedia/ CDC (public domain)

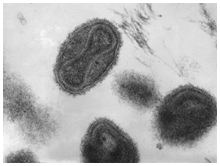

Characterized as “The Speckled Monster,” smallpox first emerged as a pandemic disease threat in ancient East Asia and then spread through the Middle East, India and then to Africa and Europe and began to spread in the Americas in the 16th century. Smallpox is an acute, highly contagious, self-limiting and naturally immunizing infectious disease caused by the Variola major, or the less severe Variola minor, virus types. There are no known non-human reservoirs of the smallpox virus, which spreads through infected droplets and contact with infectious rashes and blisters.

Image source: Museum of Health Care (unaccessioned)

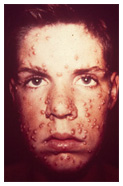

The disease starts like any other “flu,” then rashes and blisters appear, first inside the mouth and then on the skin, starting on the face and spreading down the body. The blisters then rupture, spew infectious pus and eventually crust over, leaving permanent scarring. In severe Variola major cases the virus attacks the vital systems of the body, leading to a variety of serious complications and often death; in unvaccinated cases, the mortality rate generally ranges between 30 and 35%, but can be much higher.

“Bloody Smallpox” – Windsor, Ontario, 1924

Small-Pox and Vaccination: A Popular Treatise by J.J. Heagerty, published by Department of Health, Canada, in 1924. Cover and photo showing confluent smallpox, Windsor,1924.

Small-Pox and Vaccination: A Popular Treatise by J.J. Heagerty, published by Department of Health, Canada, in 1924. Cover and photo showing confluent smallpox, Windsor,1924."Today we have no conception of the meaning of the word 'smallpox'." So wrote Dr. John Heagerty of Canada’s Federal Public Health Service in the booklet, Small-Pox and Vaccination: A Popular Treatise, published in the wake of a deadly smallpox epidemic that struck the Windsor, Ontario area in 1924. Of the 67 cases reported, 32 died and the death rate among the unvaccinated was a striking 71%. As was reported when the crisis had finally eased, “The epidemic, which started in the home of Gordon Deneau, a furniture mover, in January, is the worst since the epidemic in Montreal in 1885. All deaths which occurred were of unvaccinated persons. The only persons who attended the funeral of Deneau and escaped infection were those vaccinated” (The Globe, March 11, 1924, p. 3). Indeed, five members of the Deneau family, four brothers and one sister, lost their lives to one of the worst forms of “bloody” smallpox.

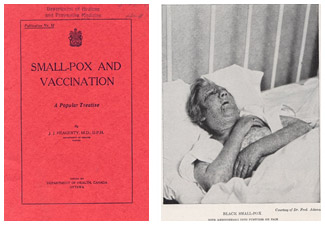

Smallpox infected mother with vaccinated child, Windsor, 1924

Smallpox infected mother with vaccinated child, Windsor, 1924Image source: J.J. Heagerty, Smallpox & Vaccination (Ottawa, 1924)

Dr. Heagerty personally investigated the 1924 Windsor epidemic and, despite its unusual severity, observed, "For us the word [smallpox] has been robbed of its terrors and we discuss the problem of smallpox in the community in a general and academic way." Yet, in the pre-vaccine days, "the word 'smallpox' blanched the cheek and brought a look of terror to the eyes. Smallpox in those days meant death. Relentless and insatiate the disease would sweep though a community mowing down all those who had not already suffered from it; killing, maiming and leaving its victims blinded or disfigured for life." Moreover, "It played a part of no little importance in the political history of Canada in the early days… Vaccination has altered all this and forgetful or ignorant of the appalling ravages of the disease in other days, we now scarcely give the subject of smallpox a thought."

The First Chapters of Smallpox in Canada

The earliest smallpox outbreak in the Americas struck in the West Indies in 1507, likely introduced by Spanish sailors. The disease then spread rapidly among the immunologically vulnerable native population of Central and South America with devastating results. Remarkably, smallpox would not be introduced into North America for another century with French and British settlers bringing the disease to the fledgling New France and New England colonies, followed by Dutch traders who inadvertently spread it north and west.

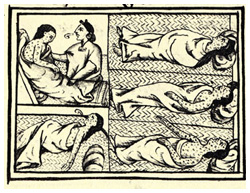

Image source: Wikipedia (public domain image)

". . . [smallpox] brought great desolation: a great many died of it. They could no longer walk about, but lay in their dwellings and sleeping places, no longer able to move or stir… And when they made a motion, they called out loudly. The pustules that covered people caused great desolation; very many people died of them, and many just starved to death; starvation reigned, and no one took care of others any longer. On some people, the pustules appeared only far apart, and they did not suffer greatly, nor did many of them die of it. But many people's faces were spoiled by it, their faces were made rough. Some lost an eye or were blinded." (Translated from the Florentine Codex)

The first smallpox epidemic in what would become Canada struck in 1616, with the natives devastated near Tadoussac, France’s first trading post in North America. The disease soon spread to other tribes in the Maritimes, James Bay and the Great Lakes region. During the 1630s, nearly every native tribe in the Great Lakes region was affected by smallpox and by 1636 the population of the Huron north of Lake Ontario had been reduced by half. The Huron, however, believed smallpox was brought into their midst by the French Jesuit priests committed to Christian conversion. But the Jesuits did their best to care for ill natives with whom they closely lived. From a 1637 entry of the Jesuit Relations:

“It was upon the return from the journey which the Hurons made to ‘Kebec’ that it started in the country – our Hurons, while again on their way up here, having thoughtlessly mixed with the Algonquins, whom they met on the route, most of whom were infected with smallpox. The first Huron who introduced it came ashore at the foot of our house, newly built on the bank of a lake – being carried thence to his own village, but a league distant from us, he straightaway died.”

During the balance of the 17th century, smallpox was always present among the native population as it spread over half of North America, taken in all directions when whole tribes fled in terror during epidemics.

Smallpox Variolation & Vaccination

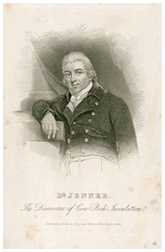

Dr. Edward Jenner (1749-1823)

Dr. Edward Jenner (1749-1823)Image source: Science Museum Group, Collections Online (public domain image).

Soon after the British conquest of New France in 1763, a way to prevent smallpox, known as “variolation,” was introduced in the colony that worked by exposing people to the disease in a controlled manner. This method, also known as “inoculation,” originated in 11th century China and India and was based on the observation that most who contracted smallpox never caught it again. Thus, if a person became infected through a scratch, they developed a much less severe form of the disease than if infected by the natural oral route of the virus. Variolation was first used in British-held Quebec in 1765 and by 1769 a concerted immunization effort had been launched among the prominent families of Montreal and Quebec and also the British troops.

There was, however, less enthusiasm for variolation among the American colonies. An inequality soon developed in immunity levels between the British troops north of the St. Lawrence River, and the English American colonial troops to the south as the American Revolution began. Soon after Washington launched his attack on Quebec in July 1775, smallpox broke out among his troops, yet the disease did not affect the immunized British forces, forcing Washington’s men to hastily retreat. Thus, it was clear that smallpox played a major role in saving Canada for the British Empire.

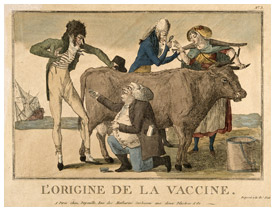

Variolation would soon be supplanted by smallpox “vaccination,” developed by Edward Jenner in Britain in 1796. Jenner observed that milkmaids rarely had pox-marked skin and discovered that exposure to a mild cowpox infection (vacca is Latin for cow) effectively immunized people against smallpox. Jenner was the first to collect the cowpox-infected material from the skin of calves to prepare a “vaccine,” and then demonstrate that the inoculation of a healthy person protected them from the disease during a smallpox outbreak. British North American natives quickly benefited from smallpox vaccination and were enthusiastic about its value.

During the late 18th and early 19th centuries, the Hudson’s Bay Company served as the de-facto public health agency across the northwest, focused especially on smallpox prevention among the native population. In particular, in 1838-39, the HBC launched an immense vaccination program across most of what is now western Canada that would limit the disease to little more than a toehold for several decades.

“The Speckled Monster” in Canada

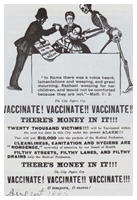

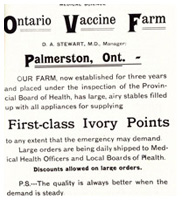

Smallpox vaccine was used widely in Canada during the early 1800s, although it soon became neglected. Low immunization levels led to persistent outbreaks that climaxed in Canada’s worst smallpox epidemic in 1885, when more than 3,000 people died from the disease in the Montreal area. Anti-vaccine sentiments mixed with religious and French-English political tensions helped fuel the crisis. After this epidemic spread into parts of Eastern Ontario, the Ontario Vaccine Farm in Palmerston was established to provide a supply of smallpox vaccine for the province and beyond. The Ontario Vaccine Farm operated until 1916, when responsibility for supplying smallpox vaccine in Canada was assumed by Connaught Laboratories, which had been established as a self-supporting part of the University of Toronto in 1914.

Anti-Vaccination poster, 1885

Anti-Vaccination poster, 1885Image source: M. Bliss, Plague: The Story of Smallpox in Montreal (Toronto: HarperCollins, 1991)

(public domain image)

Wax model of vaccinated infant’s arm after 10th day, 1850s

Wax model of vaccinated infant’s arm after 10th day, 1850sImage source: Museum of Health Care, accession #997002031

Ontario Vaccine Farm advertisement,c. 1889

Ontario Vaccine Farm advertisement,c. 1889Image source: Medical Science (Feb. 1889) in B. Craig, “Smallpox in Ontario” in Health, Disease and Medicine: Essays in Canadian History (Hannah Institute, 1984)

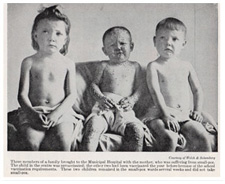

Smallpox in Windsor, 1924, showing vaccinated and unvaccinated siblings.

Smallpox in Windsor, 1924, showing vaccinated and unvaccinated siblings.Image source: J.J. Heagerty, Small-Pox and Vaccination (Ottawa, 1924)

Despite the ample and free supply of smallpox vaccine available in Canada, it was not always used. A further dramatic example of what could happen when vaccination was neglected was clearly seen in the Windsor, Ontario area in early 1924. Of the 67 smallpox cases reported, 32 died and the death rate among the unvaccinated was a striking 71%.

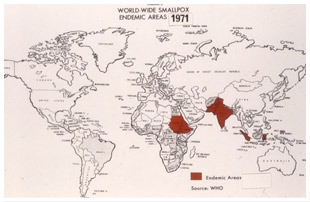

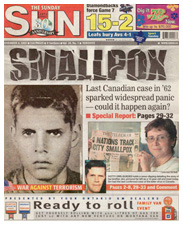

Twentieth century smallpox incidence in Canada reached a peak of 3,300 cases in 1927, but fell sharply to zero by the mid-1940s. The last smallpox case in Canada occurred in 1962 when a teenage boy brought the disease home with him after a trip to Brazil. It was a mild case, but with smallpox very rare in North America at the time, this infected teen, who travelled by train through the eastern U.S. and into Canada, set off public health alarms and a mass vaccination campaign on both sides of the border. This single case underscored the vulnerability to smallpox in North America while the disease remained endemic anywhere else on the planet.

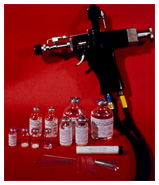

Image source: Sanofi Pasteur Canada

Canada and Smallpox Eradication

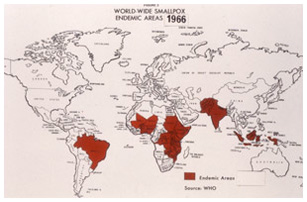

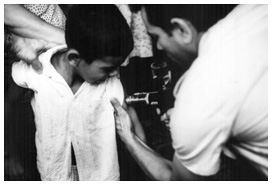

Though eradicated in Canada by the 1940s, smallpox remained a major threat in many parts of the world, largely due to poor quality vaccine. There were many regional efforts to eradicate smallpox through compulsory vaccination laws with varying levels of success. The first hemisphere-wide effort was launched in 1950 by the Pan American Health Organization, which reduced the disease to only Argentina, Brazil, Columbia and Ecuador. A global eradication initiative was first proposed in 1953 by Dr. Brock Chisholm, a Canadian who was the WHO’s first Director-General. However, the idea did not progress until a limited program began in 1959, when there were still some 50 million cases and 2 million deaths from smallpox globally each year. Energized after the imported case from Brazil into the U.S. and Canada in 1962, the WHO launched a comprehensive smallpox eradication program in 1966-67.

This intensified effort was strengthened by the contributions of Connaught Laboratories (which remained part of the University of Toronto until 1972), especially Dr. Robert J. Wilson and Dr. Paul Fenje. They worked closely with the Director of the WHO eradication program, Dr. Donald A. Henderson, whose mother was as a nurse during the 1924 Windsor smallpox epidemic. Wilson and Fenje worked closely with vaccine producers in Latin America to improve vaccine quality, based on an international freeze-dried smallpox vaccine standard that Connaught helped establish for the WHO. Connaught also served as the international vaccine reference lab for the western hemisphere and was a major source of freeze-dried vaccine for the eradication campaign.

Image source: Sanofi Pasteur Canada Archives

Archival Video: Smallpox Vaccine production, Connaught Laboratories Film, 1966:

The last recorded case of smallpox occurred in Somalia. Ali Maow Maalin, who was a cook, developed smallpox on October 26, 1977. After two years of careful surveillance for additional cases, global eradication of smallpox was officially declared. It was the first disease to ever be eradicated from the planet, with only samples of the virus retained in secure laboratories for research purposes.

As emphasized by Dr. Henderson on the occasion of Dr. Fenje's retirement in 1979, "Directly and indirectly, the ammunition for the campaign bore the indelible stamp – 'made in Canada.' To a once-Canadian, it was always a personal source of pride."

In 1980, with smallpox officially eradicated, Connaught began the process of shutting down its smallpox vaccine production facilities, the last lots prepared for Canada’s contribution to a proposed WHO stockpile. However, production was not completed when the stockpile plan was abandoned, leaving 15 Vaccinia pulps – the base material for smallpox vaccine - in deep freeze storage, but with ultimate plans for incineration. Connaught’s Medical Director, however, strongly recommended that the Vaccinia pulps be kept. He wrote, “It surely will not be a great problem to keep the seed virus and pulps for some time to come and at least in this way we might have something to fall back on so as to be able to prepare our licensed product.” The pulps were saved and kept in the deep freeze, undisturbed, for the next 21 years. The terrorist attacks of ‘9/11” - and the potential use of smallpox as a bio-terrorist weapon - prompted the retrieval, testing and careful processing of the Vaccinia pulps to expedite the preparation of a new Canadian smallpox vaccine stockpile in 2002.

Image source: Sanofi Pasteur Canada