Healing Threads: Occupational Therapy during the World Wars

In my last blog post, titled ‘The Early Years of Occupational Therapy in Kingston,’ I discussed the use of occupations such as work and craft in psychiatric asylums in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Occupations during this period were used to engage patients in work that was distracting and often financially beneficial for the institution. Although work, art, and craft were present in health care spaces at the turn of the twentieth century, occupational therapy as a distinct medical field largely formed in response to World War I (1914–1918). Continuing my Margaret Angus research about occupational therapy in Canada, this month I will trace the professionalization of occupational therapy and how craft played a pivotal role in the rehabilitation of soldiers following the devastation of the First and Second World Wars. Although this blog post focuses on craft, it is important to note that occupational therapy involves a wide range of activities to rehabilitate the mind and body and to teach skills that are considered essential for employment and participation in all other aspects of life. Wartime occupational therapists developed a broad skillset to individualize treatment. Craft was not their only rehabilitation tool, but it was an important one.

The World Wars and the Association of Occupational Therapists

Canada entered World War I with Great Britain in 1914. Patriotism was running high and in the early months of the war thousands of Canadians enlisted, many believing that the conflict would end quickly.[1] Initially, Canadian hospitals felt far removed from the war as soldiers were treated in overseas field hospitals close to the front.[2] A year into the conflict, however, the true scale of the war came into focus. Soldiers were leaving the front with serious, debilitating wounds, infections, diseases, and mental scars that were too complex to be treated in field hospitals. As the war continued, it became increasingly clear that thousands of men would not be able to return to fighting and required long term treatment and convalescent care back home.[3] The Military Hospitals Commission was established in 1915 to manage soldiers’ care.[4] Temporary military hospitals were created to house and treat the influx of returning soldiers. In Kingston, temporary hospitals were set up in familiar locales including Morton’s brewery (which now houses the Tett Centre for Creativity and Learning), and Kingston Hall and Grant Hall at Queen’s University, among others.[5]

Of the 650,000 Canadians who enlisted, 66,000 were killed and 172,000 were wounded by the end of the war.[6] In response to overwhelming medical pressures, new treatments and technologies emerged including plastic surgery, blood transfusions, as well as innovative treatments for broken bones, gas attacks, and shell shock.[7] The field of occupational therapy also emerged during this period with the creation of training programs for ward aides. As soldiers returned home with serious physical and mental injuries, there was increasing concern over their ability to reintegrate into society and pursue employment.[8] In 1918 the Department of Soldiers’ Civil Re-establishment developed training programs for ward aides, also referred to as occupational aides, who used craft to improve soldiers’ fine motor skills and confidence.[9] The first programs were offered in Toronto and Montreal and between 1918 and 1919 over 300 ward aides were employed in military hospitals across Canada.[10] Following the war, ward aides were renamed occupational therapists and they worked in a wide range of medical settings. In 1926, the Canadian Association of Occupational Therapists was created and the field expanded with university courses and an academic journal.[11] By 1939, the Association represented 1,000 Canadian therapists and was called upon to rehabilitate injured soldiers for a second time at the outbreak of World War II (1939-1945).[12]

Craft for Rehabilitation

Common occupational activities offered to soldiers in convalescent care included fibre crafts such as knitting and weaving, needlework including cross stitch and embroidery, pottery, and carpentry. For soldiers whose injuries kept them bedbound, weaving, knitting, and needlework were often the most accessible forms of craft and greatly improved fine motor skills and coordination. Looms were particularly useful tools as they could be adapted to rest on the chest to be worked while lying down or could be set up on a bed so weaving could be completed in a seated position.[13] In 1942, the Canadian loom manufacturing company Nilus Leclerc produced looms specifically designed for the rehabilitation of injured soldiers (referred to as ‘exercise looms’) and supplied weaving equipment to recovery programs across Canada, the United States, and Great Britain.[14] A series of photographs taken by Ronny Jaques in 1945 and held in the collections of Library and Archives Canada document the occupational therapy division of Scarborough Hospital, showing men at work on floor looms and displaying handwoven items.

Occupational aides selected the looms best suited for a soldiers’ condition, provided instruction for using various weaving tools, and oversaw the completion of their projects, guiding them through the cognitive and physical demands of learning a new skill while healing.

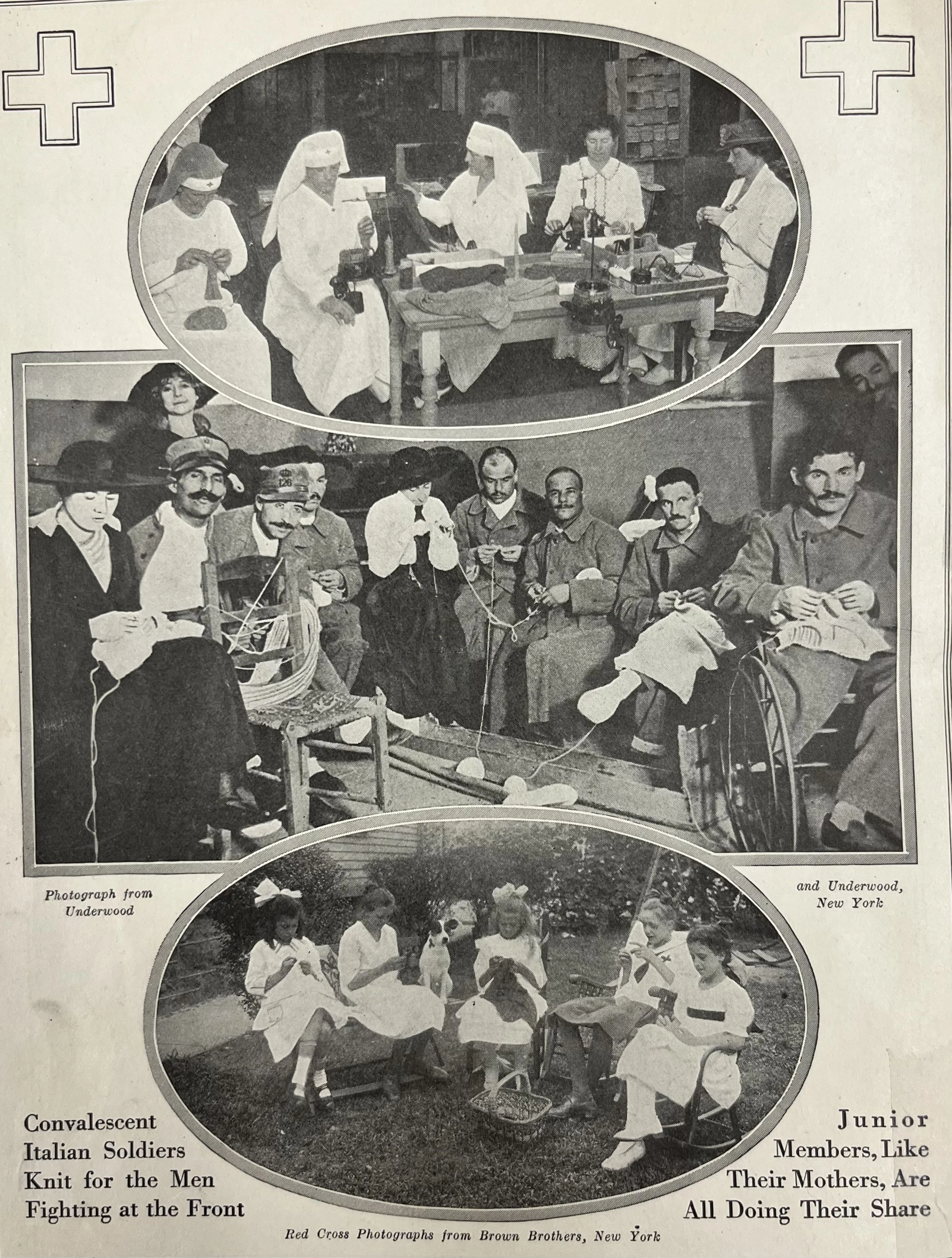

Some crafts also directly supported men on the front lines. Women’s contributions to the war effort through knitting are well documented. However, injured soldiers were also encouraged to cast on projects while recovering. The first page of the American Red Cross’ 1917 knitting pamphlet titled the “Priscilla War Work Book,” includes a photograph of Italian soldiers in a military hospital with the caption “Convalescent Italian soldiers knitting for men on the front.”

Both on the home front and in military hospitals, knitters produced wool garments such as scarves, socks, gloves, balaclavas, and caps, and even medical staples such as cotton bandages.[15] Making essential items was thought to allow soldiers to feel productive and useful to those fighting on the front while offering them a simple and repetitive activity to keep their hands and minds occupied.[16]

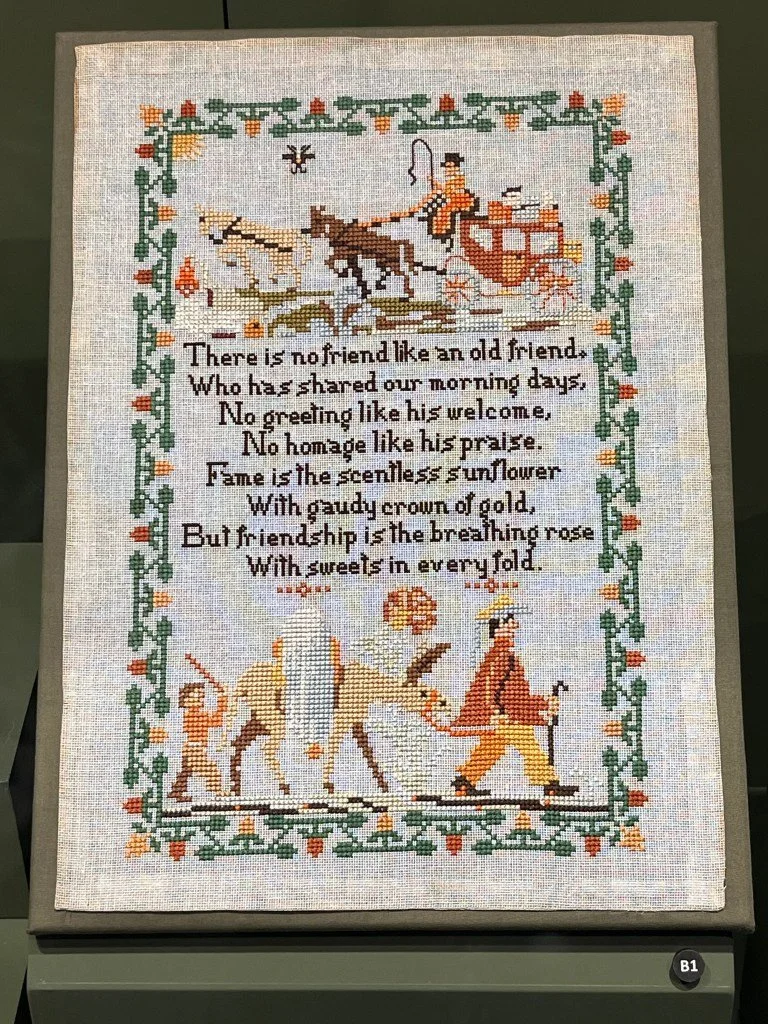

Needlework in the form of embroidery and cross-stitch was also a common occupational activity. The Museum of Health Care’s collections contain examples of needlework projects with local significance. In one example, a wounded World War One soldier created a cross-stitch with an excerpt of an Oliver Wendell Holmes poem titled “No Time Like the Old Time,” including a decorative border and scenes of rural life. The piece was gifted to Nursing Sister Helen Glasgow who graduated from the Kingston General Hospital School of Nursing class of 1910.[17] Glasgow served as a Canadian Nursing Sister in France during the war and received the stitched poem from a soldier she treated.[18]

The second example is a tablecloth that was embroidered by Frederick Percy Ovenden (1894 -1972) between 1917 and 1918 (Figure 5). Ovenden contracted tuberculosis overseas while fighting in World War One and was treated at the Sir Oliver Mowat Memorial Tuberculosis Sanatorium Hospital in Portsmouth Village upon his return to Canada.[19]

Crafting while healing provided soldiers with several benefits. Doctors and nurses reported that soldiers who made things regained their physical strength and hand mobility more quickly and became incredibly passionate about their projects.[20] This passion often translated into increased self-esteem.[21] There was also another key benefit to learning new skills. Many soldiers had significant injuries that prevented them from returning to their previous jobs or seeking work. In Great Britain, a whole industry was created to support veterans called the Disabled Soldiers’ Embroidery industry.[22] On a smaller scale, in Canada there were exhibitions of veterans’ crafts and visitors could purchase items on display.[23] Occupational therapy opened new avenues for soldiers who were starting the difficult task of reintegrating into civilian life after experiencing some of the most devastating wars in history.

Bibliography

“An army of knitters in support of the war effort,” Canadian War Museum, November 27, 2023, https://www.warmuseum.ca/articles/an-army-of-knitters-in-support-of-the-war-effort.

Bush, Mary Polityka “Knit, Purl, Heal,” Piecework, October 30, 2023, https://pieceworkmagazine.com/knit-purl-heal/.

Drazilov, Victor. “The History of Temporary Military Hospitals in Kingston.” Museum of Health Care Blog, November 13, 2021, https://museumofhealthcare.blog/the-history-of-temporary-military-hospitals-in-kingston/.

“First World War,” Government of Canada, revised March 6, 2024, https://www.veterans.gc.ca/en/remembrance/wars-and-conflicts/first-world-war.

Friedland, Judith. “Program History: Canadian Occupational Therapy Education Begins at U of T.” Occupational Science and Occupational Therapy. University of Toronto, 2006. https://ot.utoronto.ca/program-history.

Friedland, Judith. Restoring the Spirit: The Beginnings of Occupational Therapy in Canada, 1890-1930. Kingston: McGill-Queen's University Press, 2011.

Friedland, Judith, Isobel Robinson, and Thelma Cardwell. “In the Beginning: CAOT from 1926-1939.” Occupational Therapy Now 3, no. 1 (January/February 2001): 15-19.

“History,” Leclec Looms, accessed June 11, 2025, http://www.leclerclooms.com/histo/N_B_HISTORY_01.htm

Museum of Health Care, “embroidered panel,” accession number 005023001 research notes, https://mhc.andornot.net/en/list?q=Helen+Glasgow+&p=1&ps=20.

Museum of Health Care, “embroidered tablecloth from the Mowat Sanatorium” research file.

Marie-Hélène Naud, “Art Therapy for Veterans,” La Guilde Archives, October 31, 2021, https://laguilde.com/en/blogs/saviez-vous-que/art-therapie.

McBrinn, Joseph. “‘The work of masculine fingers:’ the Disabled Soldiers’ Embroidery Industry, 1918-1955.” Journal of Design History 31, no. 1 (October 2016): 1-23.

“Medical Progress: Canada and the First World War.” Canadian War Museum, accessed June 11, 2023, https://www.warmuseum.ca/firstworldwar/history/life-at-the-front/medicine/medical-progress/.

Endnotes

[1] “First World War,” Government of Canada, revised March 6, 2024, https://www.veterans.gc.ca/en/remembrance/wars-and-conflicts/first-world-war.

[2] Judith Friedland, Restoring the Spirit: The Beginnings of Occupational Therapy in Canada, 1890-1930. (Kingston: McGill-Queen's University Press, 2011), 87.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Victor Drazilov, “The History of Temporary Military Hospitals in Kingston,” Museum of Health Care Blog, November 13, 2021, https://museumofhealthcare.blog/the-history-of-temporary-military-hospitals-in-kingston/.

[6] “First World War,” Government of Canada.

[7] “Medical Progress: Canada and the First World War,” Canadian War Museum, accessed June 11, 2023, https://www.warmuseum.ca/firstworldwar/history/life-at-the-front/medicine/medical-progress/

[8] Friedland, Restoring the Spirit, 88.

[9] Judith Friedland, “Program History: Canadian Occupational Therapy Education Begins at U of T,” University of Toronto, July 17, 2006, https://ot.utoronto.ca/program-history.

[10] Judith Friedland, Isobel Robinson, and Thelma Cardwell, “In the Beginning: CAOT from 1926-1939,” Occupational Therapy Now 3, no. 1 (January/February 2001): 15.

[11] Ibid., 16-17.

[12] Ibid., 18.

[13] Examples can be seen at https://laguilde.com/en/blogs/saviez-vous-que/art-therapie

[14] “History,” Leclec Looms, accessed June 11, 2025, http://www.leclerclooms.com/histo/N_B_HISTORY_01.htm

[15] “An army of knitters in support of the war effort,” Canadian War Museum, November 27, 2023, https://www.warmuseum.ca/articles/an-army-of-knitters-in-support-of-the-war-effort.

[16] Mary Polityka Bush, “Knit, Purl, Heal,” Piecework, October 30, 2023, https://pieceworkmagazine.com/knit-purl-heal/.

[17] Museum of Health Care, “embroidered panel,” accession number 005023001 research notes, https://mhc.andornot.net/en/list?q=Helen+Glasgow+&p=1&ps=20.

[18] Ibid.

[19] Museum of Health Care, “embroidered tablecloth from the Mowat Sanatorium” research file.

[20] Marie-Hélène Naud, “Art Therapy for Veterans,” La Guilde Archives, October 31, 2021, https://laguilde.com/en/blogs/saviez-vous-que/art-therapie

[21] Ibid.

[22] Joseph, McBrinn. “‘The work of masculine fingers:’ the Disabled Soldiers’ Embroidery Industry, 1918-1955,” Journal of Design History 31, no. 1 (October 2016): 1-23.

[23] Naud, “Art Therapy for Veterans.”

About the Author

Shaelagh Cull (MARF 2025)

Shaelagh Cull is in independent researcher who specializes in the history of craft in Canada. She holds a Master’s of Art History from Queen’s University and is an active member of the Kingston Handloom Weavers and Spinners Guild. As the 2025 Margaret Angus Research Fellow, Shaelagh will trace the development of occupational therapy, exploring how weaving and other crafts were used in medical settings in Kingston and across Canada. She is excited to bring this history to life with fascinating objects from the Museum’s collections.