Mary Alice Peck, Mary Black, and Women’s Contributions to Occupational Therapy

Two names have repeatedly come up in the research for my Margaret Angus fellowship project about occupational therapy in Canada: Mary Alice Peck and Mary Black. While my previous blog posts have focused on major historical periods in the development of occupational therapy in Canada (the asylum reform movement of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries and the World Wars), this post focuses on these two influential women. Peck and Black were both significant figures in the development of occupational therapy in Canada, although they epitomize different aspects of women’s roles in the field. Mary Alice Peck represents the push by middle and upper-class women and women’s groups to fund and provide materials for occupational therapy programs, while Mary Black practiced as a therapist and worked to professionalize the field in both Canada and the United States. Through their stories, we learn how women financially supported the creation of occupational therapy programs in hospitals and communities and what everyday life looked like for a twentieth-century occupational therapist.

Mary Alice Peck (1855-1943)

In the twentieth century, there was an association between women and caring professions due to social, moral, and religious pressures on women to provide charity to those in need. This prompted many wealthy middle-class women to form and fund organizations related to rehabilitation. Many of these were volunteer organizations. However some women working in careers such as nursing and occupational therapy received payment for their work. Mary Alice Peck was born to a wealthy family in Montréal and is best known for co-founding the Canadian Handicrafts Guild in 1905, but she was also deeply interested and invested in the healing potential of crafts. This interest began when she toured Europe as a child and, on her travels, saw a girl with physical disabilities in an art gallery who was replicating a painting on a weaving loom.[1] Recounting the story later in her life, Peck noted how joyful the child looked while weaving.[2] This experience seemingly underscored the importance of craft for Peck and inspired her to push for craft spaces in medical settings.

Through letters held in the archives of Le Guilde in Montréal, we know that Peck began advocating for craft spaces in sanitaria in 1910, although the Canadian Handicrafts Guild may have been involved in this work earlier.[3] In one example, Peck corresponded with A.T. Hobbs, medical superintendent of Homewood Sanitarium in Guelph, Ontario, about offering craft classes to patients, a request that Hobbs initially denied due to lack of space before he committed to constructing a separate arts and crafts building.[4] When the space was finished, Hobbs sought Peck’s recommendations for craft demonstrations.[5]

Peck’s attention turned to the war effort during World War I. In 1916 she wrote a pamphlet called “Party Occupational Therapy: Handicrafts (or Cottage Industries) for Soldiers,” which described the types of crafts that could be useful for the rehabilitation of soldiers.[6] Through this pamphlet, Peck also emphasized the potential for soldiers to sell and create a cottage industry from their crafts. Following her death in 1943, the Canadian Handicrafts Guild continued Peck’s occupational efforts. The Guild’s president, Galt Durnford, collaborated closely with the Occupational Therapy Centre in Montréal to ensure that soldiers had access to craft materials and education, and the Canadian Handicrafts Guild supported occupational therapy training programs and hosted promotional exhibitions of soldiers’ craft, providing veterans with a place to promote and sell their work.[7]

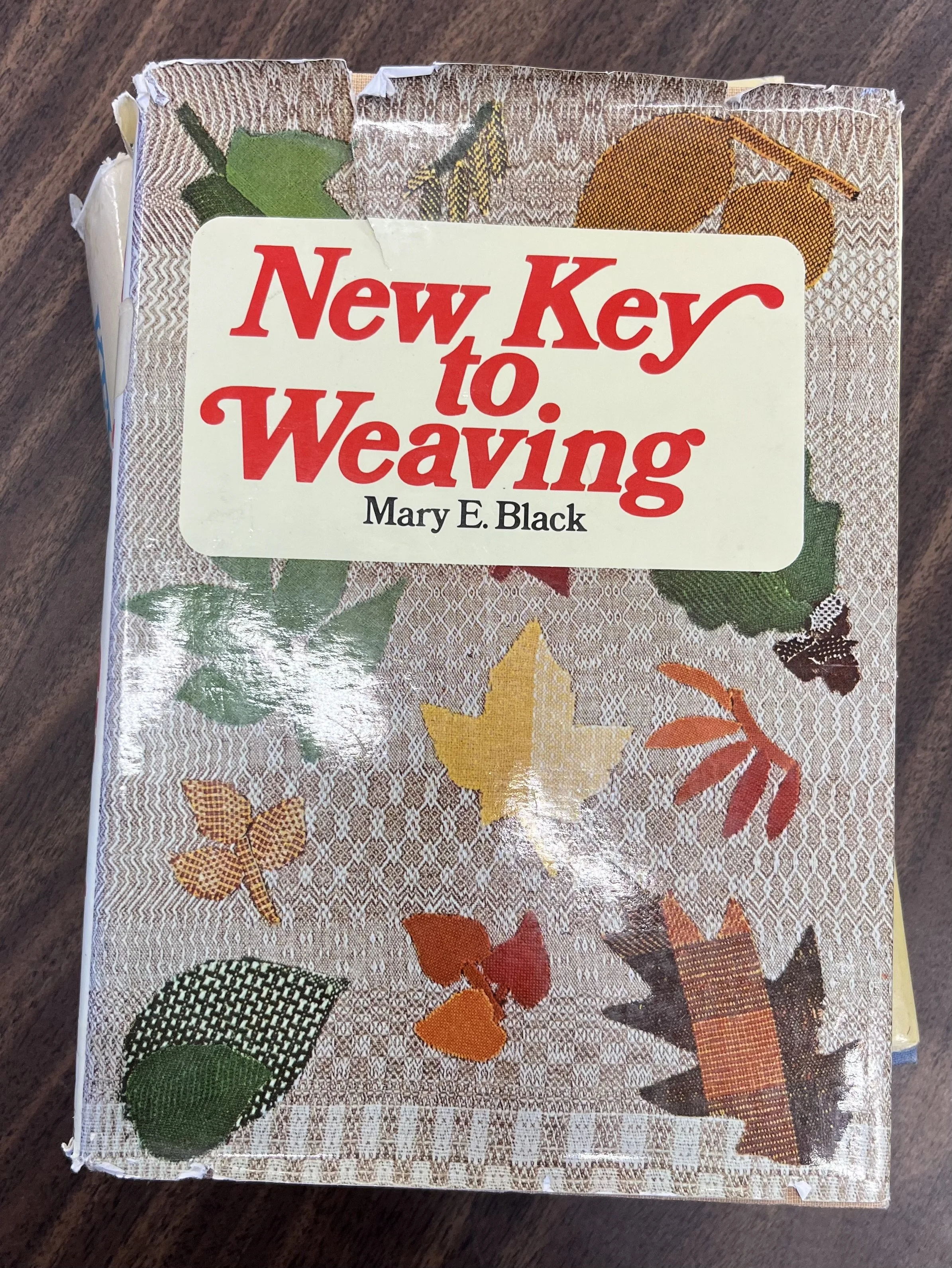

Figure 1: Mary Black’s influential text The Key to Weaving, which was first published in 1945.

Mary Black (1895-1988)

Mary Black’s career followed the trajectory of many of her occupational therapy contemporaries in the mid-twentieth century. But Black’s passion for her work, particularly the use of craft in occupational therapy, resulted in a successful publishing career which means that we have more documentation of her life and work. Like many early twentieth-century occupational therapists, Black started in craft before working in the medical field. Born on Nantucket Island, Massachusetts but spending most of her childhood in Wolfville, Nova Scotia, Black was captivated by handicrafts, and especially weaving, from an early age.[8] When she was only eleven, she decided to collect rushes around her family cottage to create a mat as a gift for her parents.[9] In a letter to the editor of Canadian Hobby-Craft Magazine, she referred to weaving as her ‘first love’ – one she shared in her therapy practice.[10]

During World War I, Black became involved in activities on the home front, volunteering for the Red Cross and organizing local events to benefit the war effort in Wolfville.[11] While volunteering, Black saw the work of early occupational therapists first-hand and immediately sought out training programs.[12] In 1919, Black enrolled in McGill University’s ward occupational aide program where she trained in various crafts that might prove useful while working with patients, including basketry, book binding, raffia, stenciling, woodcarving, weaving, and more.[13] She completed her studies in three months and began working for the Department of Soldiers’ Civil Re-establishment who posted her at the Nova Scotia Sanatorium in Kentville, where she facilitated occupational activities for 48 patients.[14] The following year, Black was reassigned to the Nova Scotia Hospital, a mental health institution in Halifax, where she worked with both veterans and civilians.[15] On an average day, Black presented four classes (likely workshops discussing crafts) for around 55 patients and spent the rest of her time in the wards, teaching basketry, knitting, beading, and other crafts at patients’ bedsides.[16]

In 1922 Black decided to leave Canada after being offered a job in the United States.[17] She initially started working at the Boston State hospital and moved to various hospitals in Massachusetts and Michigan where she worked as the director of occupational therapy at Traverse City Hospital.[18] She also held executive positions in the Michigan and Wisconsin Occupational Therapy Associations and was a regular contributor to the American Journal of Occupational Therapy.[19] Black decided to return to Nova Scotia in 1943 and shifted her career into professional weaving. Her 1945 instructional book The Key to Weaving became one of the most influential weaving texts in Canada and was followed by several other weaving related publications (Figure 1).[20] Today, she is remembered equally for her contributions to occupational therapy and weaving.

Mary Alice Peck and Mary Black are only two examples out of hundreds of women who contributed to the field of occupational therapy, whether as therapists or through promotion or advocacy. More research is needed to piece together the stories of the many other women who worked in or otherwise contributed to this field. Women’s contributions to the history of health care remains understudied, leaving many unanswered questions. There is more of this story waiting to be uncovered.

Endnotes

[1] Ellen Mary Easton McCloud, In Good Hands: The Women of the Canadian Handicrafts Guild (Kingston: McGill-Queen's University Press, 1999), 16.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Marie-Hélène Naud, “Art Therapy for Veterans,” Le Guilde, October 31, 2021, https://laguilde.com/en/blogs/saviez-vous-que/art-therapie.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Nova Scotia Archives and Records and Atlantic Spinners and Handweavers, “Mary E. Black: Key to Weaving Collection,” accessed July 25, 2025, https://web.archive.org/web/20110721150813/http://www.parl.ns.ca/ash/pdf/MEBbrochure.pdf

[9] Contest Letter printed in Canadian Hobby-Craft Magazine, 1952, Mary E. Black Nova Scotia Archives MG 1 Vol. 2883 153

[10] Ibid.

[11] Judith Friedland, Restoring the Spirit: The Beginnings of Occupational Therapy in Canada, 1890-1930. (Kingston: McGill-Queen's University Press, 2011), 142.

[12] Ibid.

[13] Peter L. Twohig, “Once a Therapist, Always a Therapist: The Early Career of Mary Black, Occupational Therapist,” Atlantis 28 vol. 1 (Fall/Winter 2003), 109.

[14] Ibid.

[15] Ibid.

[16] Ibid.

[17] Ian McKay, The Quest of the Folk: Antimodernism and Cultural Selection in Twentieth-Century Nova Scotia. (Montreal: McGill-Queen's University Press, 1994), 165.

[18] Twohig, “Once a Therapist, Always a Therapist,” 110.

[19] Friedland, Restoring the Spirit, 144.

[20] Ibid.

Bibliography

Contest Letter printed in Canadian Hobby-Craft Magazine, 1952, Mary E. Black Nova Scotia Archives MG 1 Vol. 2883 153.

Friedland, Judith. Restoring the Spirit: The Beginnings of Occupational Therapy in Canada, 1890-1930. Kingston: McGill-Queen's University Press, 2011.

McCloud, Ellen Mary Easton. In Good Hands: The Women of the Canadian Handicrafts Guild. Kingston: McGill-Queen's University Press, 1999.

McKay, Ian. The Quest of the Folk: Antimodernism and Cultural Selection in Twentieth-Century Nova Scotia. Montreal: McGill-Queen's University Press, 1994.

Naud, Marie-Hélène. “Art Therapy for Veterans.” Le Guilde, October 31, 2021, https://laguilde.com/en/blogs/saviez-vous-que/art-therapie.

Nova Scotia Archives and Records and Atlantic Spinners and Handweavers. “Mary E. Black: Key to Weaving Collection.” Accessed July 25, 2025, https://web.archive.org/web/20110721150813/http://www.parl.ns.ca/ash/pdf/MEBbrochure.pdf

Twohig, Peter L. “Once a Therapist, Always a Therapist: The Early Career of Mary Black, Occupational Therapist.” Atlantis 28 vol. 1 (Fall/Winter 2003): 106–17.

About the Author

Shaelagh Cull (MARF 2025)

Shaelagh Cull is in independent researcher who specializes in the history of craft in Canada. She holds a Master’s of Art History from Queen’s University and is an active member of the Kingston Handloom Weavers and Spinners Guild. As the 2025 Margaret Angus Research Fellow, Shaelagh will trace the development of occupational therapy, exploring how weaving and other crafts were used in medical settings in Kingston and across Canada. She is excited to bring this history to life with fascinating objects from the Museum’s collections.